The years from 1991 to 1998 were special ones in which to be a Star Wars fan. For during these years, more so than during any other time in the franchise’s existence, Star Wars truly belonged to its fans.

The period just before this one is sometimes called the “Dark Period” or the “Dark Ages” by the fans of today. After 1983’s Return of the Jedi, that concluding installment in the original trilogy of films, George Lucas, Star Wars‘s sometimes cantankerous creator, insisted that he was done with his most beloved creation. A few underwhelming television productions aside, he stayed true to his word in the years that followed, whilst also refusing anyone else the right to play in his playground; even Kenner Toys was denied its request to invent some new characters and vehicles with which to freshen up the action-figure line. So, Star Wars gradually faded from the mass-media consciousness, much like the first generation of videogames that so infamously crashed the same year Return of the Jedi dropped. But no Nintendo came along to revive Star Wars‘s fortunes, for the simple reason that Lucas refused to allow it. The action figures that had revolutionized the toy industry gathered dust and then slowly disappeared from store shelves, to be replaced by cynical adjuncts to Saturday-morning cartoons: Transformers, He-Man, G.I. Joe. (Or, perhaps better said, the television shows were adjuncts to the action figures: the old scoffer’s claim that Star Wars had been created strictly to sell toys was actually true in their case.)

The biggest Star Wars project of this period wasn’t any traditional piece of media but rather a theme-park attraction. In a foreshadowing of the franchise’s still-distant future, Disneyland in January of 1987 opened its Star Wars ride, whose final price tag was almost exactly the same as that of the last film. Yet even at that price, something felt vaguely low-rent about it: the ride had been conceived under the banner of The Black Hole, one of the spate of cinematic Star Wars clones from the films’ first blush of popularity, then rebranded when Disney managed to acquire a license for The Black Hole’s inspiration. The ride fit in disarmingly well at a theme park whose guiding ethic was nostalgia for a vanished American past of Main Streets and picket fences. Rather than remaining a living property, Star Wars was being consigned to the same realm of kitschy nostalgia. In these dying days of the Cold War, the name was now heard most commonly as shorthand for President Ronald Reagan’s misconceived, logistically unsustainable idea for a defensive umbrella that would make the United States impervious to Soviet nuclear strikes.

George Lucas’s refusal to make more Star Wars feature films left Lucasfilm, the sprawling House That Star Wars Built, in an awkward situation. To be sure, there were still the Indiana Jones films, but those had at least as much to do with the far more prolific cinematic imagination of Steven Spielberg as they did with Lucas himself. When Lucas tried to strike out in new directions on his own, the results were not terribly impressive. Lucasfilm became as much a technology incubator as a film-production studio, spawning the likes of Pixar, that pioneer of computer-generated 3D animation, and Lucasfilm Games (later LucasArts), an in-house games studio which for many years wasn’t allowed to make Star Wars games. The long-running Star Wars comic book, which is credited with saving Marvel Comics from bankruptcy in the late 1970s, sent out its last issue in May of 1986; the official Star Wars fan club sent out its last newsletter in February of 1987. At this point, what was there left to write about? It seemed that Star Wars was dead and already more than half buried. But, as the cliché says, the night is often darkest just before the dawn.

The seeds of a revival were planted the very same year that the Star Wars fan club closed up shop, when West End Games published Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game, a tabletop RPG. Perhaps because it addressed such a niche segment of the overall entertainment marketplace, it was allowed more freedom to expand upon the extant universe of Star Wars than anything that had come before from anyone not named George Lucas. Although its overall commercial profile would indeed remain small in comparison to the blockbuster films and toys, it set a precedent for what was to come.

In the fall of 1988, Lou Aronica, head of Bantam Books’s science-fiction imprint Spectra, sent a proposal to Lucas for a series of new novels set in the Star Wars universe. This was by no means an entirely original idea in the broad strokes. The very first Star Wars novel, Alan Dean Foster’s Splinter of the Mind’s Eye, had appeared just nine months after the first film, having been born as a script treatment for a potential quickie low-budget sequel if the movie should prove modestly but not extremely successful. After it, a handful of additional paperbacks starring Han Solo and Lando Calrissian had been published. But Aronica envisioned something bigger than those early coattail-riders, a series of true “event” novels. “We can’t do these casually,” he wrote to Lucas. “They have to be as ambitious as the movies were. This body of work is too important to popular culture to end with these three movies.”

He knew it was a shot in the dark. Thus he was disappointed but not overly surprised when he heard nothing back for months; many an earlier proposal for doing something new with Star Wars had fallen on similarly deaf ears. Then, out of the blue, he received a grudging letter expressing interest. “No one is going to buy these,” Lucas groused — but if Bantam Books wanted to throw its money away, Lucasfilm would deign to accept a licensing royalty, predicated on a number of conditions. The most significant of these were that the books could take place between, during, or after the movies but not before; that they would be labeled as artifacts of an “Expanded Universe” which George Lucas could feel free to contradict at any time, if he should ever wish to return to Star Wars himself; and that Lucas and his lieutenants at Lucasfilm would be able to request whatever changes they liked in the manuscripts — or reject them completely — prior to their publication. All of that sounded fine to Lou Aronica.

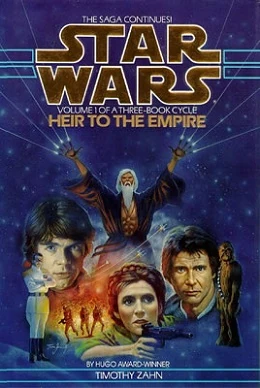

So, Heir to the Empire, the first of a trilogy of novels telling what happened immediately after Return of the Jedi, was published on May 1, 1991. Its author was Timothy Zahn, an up-and-coming writer whose short stories had been nominated for Hugo awards four times, winning once. Zahn was symbolic of the new group of creators who would be allowed to take the reins of Star Wars for the next seven years. For unlike the workaday writers who had crafted those earlier Star Wars novels to specifications, Zahn was a true-blue fan of the movies, a member of the generation who had first seen them as children or adolescents — Zahn was fifteen when the first film arrived in theaters — and literally had the trajectory of their lives altered by the encounter. Despite the Bantam Spectra imprint on its spine, in other words, Heir to the Empire was a form of fan fiction.

Heir to the Empire helped the cause immensely by being better than anyone might have expected. Even the sniffy mainstream reviewers who took it on had to admit that it did what it set out to do pretty darn effectively. Drawing heavily on the published lore of Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game as well as his own imagination, Zahn found a way to make his novel feel like Star Wars without lapsing into rote regurgitation of George Lucas’s tropes and plot lines. Grand Admiral Thrawn, his replacement for Darth Vader in the role of chief villain, was at least as interesting a character as his predecessor, whilst being interesting in totally different ways. Through him, Zahn was able to articulate an ethical code for the Empire that went beyond being evil and oppressive for the sake of it: a philosophy of political economy by no means unknown to some of the authoritarian nations of our own world, hinging on the belief that too much personal freedom leads only to anarchy and chaos and an endemic civic selfishness, making life worse for everyone. It’s a philosophy with which you can disagree — I certainly do, stridently — but it isn’t a thoughtless or even an entirely heartless one.

This is not to say that Heir to the Empire was some dry political dissertation; Zahn kept the action scenes coming, kept it fun, kept it Star Wars, striking a balance that George Lucas himself would later fail badly to establish in his own return to his science-fiction universe. The hardcover novel topped the New York Times bestseller chart, defying Lucas’s predictions of its failure, proving there was a ready market out there for new Star Wars product.

That said, very few of the Star Wars novels that would follow would match Heir to the Empire and its two sequels in terms of quality. With so much money waiting to be made, Lou Aronica’s vision for a carefully curated and edited series of event novels — perhaps one per year — fell by the wayside all too rapidly. Soon new novels were appearing monthly rather than yearly, alongside a rebooted comic book. Then they were coming even faster than that; 1997 alone saw a staggering 22 new Star Wars novels. And so the Expanded Universe fell victim to that bane of fan fictions everywhere, a lack of quality control. By the time Han Solo and Princess Leia had gotten married and produced three young Jedi of their own, who were all running around having adventures of their own in their own intertwining series of books, it was reasonable to ask whether it was all becoming much, much too much. A drought had become an indiscriminate tsunami; a trilogy of action movies had turned into All My Children.

Even when it was no better than it ought to have been, however, there was a freewheeling joy to the early Expanded Universe which is poignant to look back upon from the perspective of these latter days of Star Wars, when everything about the franchise is meticulously managed from the top down. The Expanded Universe, by contrast, was a case of by the fans, for the fans. With new movies the stuff of dreams only, they painted every corner of the universe in vivid colors of their own. The Expanded Universe could be cheesy, but it was never cynical. One could argue that it felt more like Star Wars — the original Star Wars of simple summertime fun, the one that didn’t take itself so gosh-darn seriously — than anything that has appeared under the name since 1998.

By a happy accident, a contract between Lucasfilm and Kenner Toys, giving the latter an exclusive monopoly on Star Wars “toys and games,” was allowed to lapse the same year that Heir to the Empire appeared in bookstores. Thus LucasArts, Lucasfilm’s own games division, could get in on the Expanded Universe fun. What had been a bizarre dearth of Star Wars games during the 1980s turned into a 1990s deluge almost comparable to the one taking place in novels. LucasArts released a dozen or so Star Wars games in a broad range of gameplay genres between 1993 and 1998, drawing indiscriminately both from the original movies and from the new tropes and characters of the literary Expanded Universe. Like the books, these games weren’t always or even usually masterpieces, but their unconstrained sense of possibility makes them feel charmingly anomalous in comparison to the corporate-managed, risk-averse, Disneyfied Star Wars of today.

And then, too, LucasArts did produce two games that deserve to be ranked alongside Timothy Zahn’s first trilogy of Star Wars novels as genuine classics in their field. We’ve met one of these already in an earlier article: the “space simulator” TIE Fighter, whose plot had you flying and fighting for Zahn’s more philosophically coherent version of the Empire, with both Darth Vader and Admiral Thrawn featuring in prominent roles. The other, the first-person shooter Jedi Knight, will be our subject for today.

Among other things, Jedi Knight heralded a dawning era of improbably tortured names in games. Its official full name is Star Wars: Jedi Knight — Dark Forces II, a word salad that you can arrange however you like and still have it make just about the same amount of sense. It’s trying to tell us in its roundabout way that Jedi Knight is a sequel to Dark Forces, the first Star Wars-themed shooter released by LucasArts. Just as TIE Fighter and its slightly less refined space-simulator predecessor X-Wing were responses to the Wing Commander phenomenon, Jedi Knight and before it Dark Forces put a Star Wars spin on the first-person-shooter (FPS) craze that was inaugurated by DOOM. So, it’s with Dark Forces that any Jedi Knight story has to begin.

Dark Forces was born in the immediate aftermath of DOOM, when half or more of the studios in the games industry seemed suddenly to be working on a “DOOM clone,” as the nascent FPS genre was known before that acronym was invented. It was in fact one of the first of the breed to be finished, shipping already in February of 1995, barely a year after its inspiration. And yet it was also one of the few to not just match but clearly improve upon id Software’s DOOM engine. Whereas DOOM existed on a single plane, didn’t even allow you to look or aim up or down, LucasArts’s “Jedi” engine could play host to vertiginous environments full of perches and ledges and passages that snaked over and under as well as around one another.

Dark Forces stood out as well for its interest in storytelling, despite inhabiting a genre in which, according to a famous claim once advanced by id’s John Carmack, story was no more important than it was in a porn movie. This game’s plot could easily have been that of an Expanded Universe novel.

Dark Forces begins concurrent to the events of the first Star Wars movie. Its star is Kyle Katarn, a charming rogue of the Han Solo stripe, a mercenary who once worked for the Empire but is now peddling his services to the Rebel Alliance alongside his friend Jan Ors, a space jockey with a knack for swooping in in the nick of time to save him from the various predicaments he gets himself into. The two are hired to steal the blueprints of the Death Star, the same ones that will allow the Rebels to identify the massive battle station’s one vulnerability and destroy it in the film’s bravura climax. Once their role in the run-up to that event has been duly fulfilled, Kyle and Jan then go on to foil an Imperial plot to create a new legion of super soldiers known as Dark Troopers. (This whole plot line can be read as an extended inside joke about how remarkably incompetent the Empire’s everyday Stormtroopers are, throughout this game just as in the movies. If ever there was a gang who couldn’t shoot straight…)

Told through sparsely animated between-mission cut scenes, it’s not a great story by any means, but it serves its purpose of justifying the many changes of scenery and providing some motivation to traverse each succeeding level. Staying true to the Han Solo archetype, Kyle Katarn is even showing signs of developing a conscience by the time it’s over. All of which is to say that, in plot as in its audiovisual aesthetics, Dark Forces feels very much like Star Wars. It provided for its contemporary players an immersive rush that no novel could match; this and the other games of LucasArts were the only places where you could actually see Star Wars on a screen during the mid-1990s.

Unfortunately, Dark Forces is more of its time than timeless.[1]A reworked and remastered version of Dark Forces has recently been released as of this writing; it undoubtedly eases some of the issues I’m about to describe. These comments apply only to the original version of the game. I concur with Wes Fenlon of PC Gamer, who wrote in a retrospective review in 2016 that “I spent more of my Dark Forces playthrough appreciating what it pulled off in 1995 than I did really having fun.” Coming so early in the lifespan of the FPS as it did, its controls are nonstandard and, from the perspective of the modern player at least, rather awkward, lacking even such niceties as mouse-look. In lieu of a save-anywhere system or even save checkpoints, it gives you a limited number of lives with which to complete each level, like one of the arcade quarter-eaters of yore.

Its worst issues, however, are connected to level design, which was still a bit of a black art at this point in time. It’s absurdly easy to get completely lost in its enormous levels, which have no obvious geographical through-line to follow, but are rather built around a tangled collection of lock-and-key puzzles that require lots and lots of criss-crossing and backtracking. Although there is an auto-map, there’s no easy way to project a three-dimensional space like these levels onto its two-dimensional plane; all those ladders and rising and falling passageways quickly turn into an incomprehensible mess on the map. Dark Forces is an ironic case of a game being undone by the very technological affordances that made it stand out; playing it, one gets the sense that the developers have rather outsmarted themselves. When I think back on it now, my main memory is of running around like a rat in a maze, circling back into the same areas again and again, trying to figure out what the hell the game wants me to do next.

Nevertheless, Dark Forces was very well-received in its day as the first game to not just copy DOOM‘s technology but to push it forward — and with a Star Wars twist at that. Just two complaints cut through the din of praise, neither of them having anything to do with the level design that so frustrated me. One was the lack of a multiplayer mode, an equivalent to DOOM‘s famed deathmatches. And the other was the fact that Dark Forces never let you fight with a light saber, rather giving the lie to the name of the Jedi engine that powered it. The game barely even mentioned Jedi and The Force and all the rest; like Han Solo, Kyle Katarn was strictly a blaster sort of guy at this juncture. LucasArts resolved to remedy both of these complaints in the sequel.

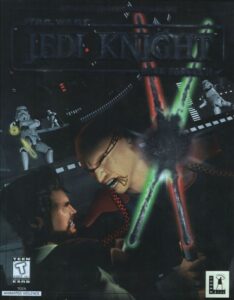

Jedi Knight actually straddles two trends in 1990s gaming, one of which has remained an evergreen staple of the hobby to this day, the other of which has long since been consigned to the realm of retro kitsch. The former is of course the FPS genre; the later is the craze for “full-motion video,” the insertion of video clips featuring real human actors into games. This “interactive movie” fad was already fast becoming passé when Jedi Knight was released in October of 1997. It was one of the last relatively big-budget, mainstream releases to embrace it.

Having written about so many of these vintage FMV productions in recent years, I’ve developed an odd fascination with the people who starred in them. These were generally either recognizable faces with careers past their prime or, more commonly, fresh-faced strivers looking for their big break, the sort of aspirants who have been waiting tables and dressing up in superhero costumes for the tourists strolling the Hollywood Walk of Fame for time immemorial, waiting for that call from their agent that means their ship has finally come in. Needless to say, for the vast majority of the strivers, a role in a CD-ROM game was as close as they ever came to stardom. Most of them gave up their acting dream at some point, went back home, and embarked on some more sensible career. I don’t see their histories as tragic at all; they rather speak to me of the infinite adaptability of our species, our adroitness at getting on with a Plan B when Plan A doesn’t work out, leaving us only with some amusing stories to share at dinner parties. Such stories certainly aren’t nothing. For what are any of our lives in the end but the sum total of the stories we can share, the experiences we’ve accumulated? All that stuff about “if you can dream it, you can do it” is nonsense; success in any field depends on circumstance and happenstance as much as effort or desire. Nonetheless, “it’s better to try and fail than never to try at all” is a cliché I can get behind.

But I digress. In Jedi Knight, Kyle Katarn is played by a fellow named Jason Court, whose résumé at the time consisted of a few minor television guest appearances, who would “retire” from acting by the end of the decade to become a Napa Valley winemaker. Court isn’t terrible here — a little wooden perhaps, but who wouldn’t be in a situation like this, acting on an empty sound stage whose background will later be painted in on the computer, intoning a script like this one?

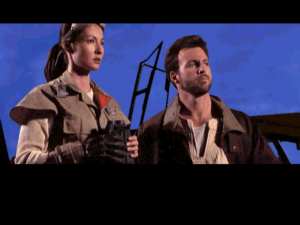

Kyle Katarn, right, with his sidekick Jan Ors. It was surely no accident that Jason Court bears a passing resemblance to Mark Hamill — who was ironically himself starring in the Wing Commander games at this time.

Ah, yes… the script. Do you remember me telling you how Timothy Zahn’s early Star Wars novels succeeded by not slavishly echoing the tropes and character beats from the films? Well, this script is the opposite of that. The first words out of any character’s mouth are those of a Light Jedi promising a Dark Jedi that “striking me down” will have unforeseen consequences, just as Obi-Wan Kenobi once said to Darth Vader. What follows is a series of reenactments of beats and entire scenes from the movies in slightly altered contexts, on a budget of about one percent the size. Kyle Katarn, now yanked out of Han Solo’s shoes and thrust into those of Luke Skywalker, turns out to have grown up on a planet bizarrely similar to Tatooine and to have some serious daddy issues to go along with an inherited light saber and undreamt-of potential in The Force. The word “derivative” hardly begins to convey the scale of this game’s debt to its cinematic betters.

For all that, though, it’s hard to really hate the cut scenes. Their saving grace is that of the Expanded Universe as a whole (into whose welcoming canon Kyle Katarn was duly written, appearing in the comics, the novels, even as an action figure of his own): the lack of cynicism, the sense that everything being done is being done out of love even when it’s being done badly. When the Jedi ignited their light sabers during the opening cut scene, it was the first time that distinctive swoosh and buzz had been seen and heard since Return of the Jedi. Even in our jaded present age, we can still sense the makers’ excitement at being allowed to do this, can imagine the audience’s excitement at being witness to it. There are worse things in this world than a community-theater re-creation of Star Wars.

The cut scenes are weirdly divorced from everything else in Jedi Knight. Many FMV productions have this same disjointed quality to them, a sense that the movie clips we watch and the game we play have little to do with one another. Yet seldom is that sense of a right hand that doesn’t know what the left is doing more pronounced than here. The Kyle of the video clips doesn’t even look like the Kyle of the rest of the game; the former has a beard, the latter does not. The divide is made that much more jarring by the aesthetic masterfulness of the game whenever the actors aren’t onscreen. Beginning with that iconic three-dimensional text crawl and John William’s equally iconic score, this game looks, sounds, and plays like an interactive Star Wars movie — whenever, that is, it’s not literally trying to be a Star Wars movie.

Certainly the environments you explore here are pure Star Wars. The action starts in a bar that looks like the Mos Eisley cantina, then sends you scampering off through one of those sprawling indoor complexes that seem to be everywhere in the Star Wars universe, all huge halls with improbably high ceilings and miles of corridors and air shafts connecting them, full of yawning gaps and precarious lifts, gun-metal grays and glittering blacks. Later, you’ll visit the streets and rooftops of a desert town with a vaguely Middle Eastern feel, the halls and courts of a fascistic palace lifted straight out of Triumph of the Will, the crawl-ways and garbage bins of a rattletrap spaceship… all very, very Star Wars, all pulsing with that unmistakable Star Wars soundtrack.

Just as Dark Forces was a direct response to DOOM, in technological terms Jedi Knight was LucasArts’s reply to id’s Quake, which was released about fifteen months before it. DOOM and Dark Forces are what is sometimes called “2.5D games” — superficially 3D, but relying on a lot of cheats and shortcuts, such as pre-rendered sprites standing in for properly 3D-modelled characters and monsters in the world. The Quake engine and the “Sith” engine that powers Jedi Knight are, by contrast, 3D-rendered from top to bottom, taking advantage not only of the faster processors and more expansive memories of the computers of their era but the new hardware-accelerated 3D graphics cards. Not only do they look better for it, but they play better as well; the vertical dimension which LucasArts so consistently emphasized benefits especially. There’s a lot of death-defying leaping and controlled falling in Jedi Knight, just as in Dark Forces, but it feels more natural and satisfying here. Indeed, Jedi Knight in general feels so much more modern than Dark Forces that it’s hard to believe the two games were separated in time by only two and a half years. Gone, for example, are the arcade-like limited lives of Dark Forces, replaced by the ability to save wherever you want whenever you want, a godsend for working adults like yours truly whose bedtime won’t wait for them to finish a level.

If you ask me, though, the area where Jedi Knight improves most upon its predecessor has nothing to do with algorithms or resolutions or frame rates, nor even convenience features like the save system. More than anything, it’s the level design here that is just so, so much better. Jedi Knight’s levels are as enormous as ever, whilst being if anything even more vertiginous than the ones of Dark Forces. And yet they manage to be far less confusing, having the intuitive through-line that the levels of Dark Forces lacked. Very rarely was I more than momentarily stumped about where to go next in Jedi Knight; in Dark Forces, on the other hand, I was confused more or less constantly.

Maybe I should clarify something at this point: when I play an FPS or a Star Wars game, and especially when I play a Star Wars FPS, I’m not looking to labor too hard for my fun. I want a romp; “Easy” mode suits me just fine. You know how in the movies, when Luke and Leia and the gang are running around getting shot at by all those Stormtroopers who can’t seem to hit the broadside of a barn, things just kind of work out for them? A bridge conveniently collapses just after they run across, a rope is hanging conveniently to hand just when they need it, etc. Well, this game does that for you. You go charging through the maelstrom, laser blasts ricocheting every which way, and, lo and behold, there’s the elevator platform you need to climb onto to get away, the closing door you need to dive under, the maintenance tunnel you need to leap into. It’s frantic and nerve-wracking and then suddenly awesome, over and over and over again. It’s incredibly hard in any creative field, whether it happens to be writing or action-game level design, to make the final product feel effortless. In fact, I can promise you that, the more effortless something feels, the more hard work went into it to make it feel that way. My kudos, then, to project leader Justin Chin and the many other hands who contributed to Jedi Knight, for being willing to put in the long, hard hours to make it look easy.

Of those two pieces of fan service that were deemed essential in this sequel — a multiplayer mode and light sabers — I can only speak of the second from direct experience. By their own admission, the developers struggled for some time to find a way of implementing light sabers in a way that felt both authentic and playable. In the end, they opted to zoom back to a Tomb Raider-like third-person, behind-the-back perspective whenever you pull out your trusty laser sword. This approach generated some controversy, first within LucasArts and later among FPS purists in the general public, but it works pretty well in my opinion. Still, I must admit that when I played the game I stuck mostly with guns and other ranged weapons, which run the gamut from blasters to grenades, bazookas to Chewbacca’s crossbow.

The exceptions — the places where I had no choice but to swing a light saber — were the one-on-one duels with other Jedi. These serve as the game’s bosses, coming along every few levels until the climax arrives in the form of a meeting with the ultimate bad guy, the Dark Jedi Jerec whom you’ve been in a race with all along to locate the game’s McGuffin, a mysterious Valley of the Jedi. (Don’t ask; it’s really not worth worrying about.) Like everything else here, these duels feel very, very Star Wars, complete with lots of villainous speechifying beforehand and lots of testing of Kyle’s willpower: “Give in to the Dark Side, Kyle! Use your hatred!” You know the drill. I enjoyed their derivative enthusiasm just as much as I enjoyed the rest of the game.

Almost more interesting than the light sabers, however, is the decision to implement other types of Force powers, and with them a morality tracker that sees you veering toward either the Dark or the Light Side of the Force as you play. If you go Dark by endangering or indiscriminately killing civilians and showing no mercy to your enemies, you gradually gain access to Force powers that let you deal out impressive amounts of damage without having to lay your hand on a physical weapon. If you go Light by protecting the innocent and sparing your defeated foes, your talents veer more toward the protective and healing arts — which, given the staggering amounts of firepower at your disposal in conventional-weapon form, is probably more useful in the long run. Regardless of which path you go down, you’ll learn to pull guns right out of your enemies’ hands from a distance and to “Force Jump” across gaps you could never otherwise hope to clear. Doing so feels predictably amazing.

Kyle can embrace the Dark Side to some extent. But as usually happens with these sorts of nods toward free will in games with mostly linear plot lines, it just ends up meaning that he foils the plans of the other Dark Jedi for his own selfish purposes rather than for selfless reasons. Cue the existentialist debates…

I’m going to couch a confession inside of my praise at this point: Jedi Knight is the first FPS I’ve attempted whilst writing these histories that I’ve enjoyed enough to play right through to the end. It took me about a week and a half of evenings to finish, the perfect length for a game like this in my book. Obviously, the experience I was looking for may not be the one that other people who play this game have in mind; those people can try turning up the difficulty level, ferreting out every single secret area, killing every single enemy, or doing whatever else they need to in order to find the sort of challenge they’d prefer. They might also want to check out the game’s expansion pack, which caters more to the FPS hardcore by eliminating the community-theater cut scenes and making everything in general a little bit harder. I didn’t bother, having gotten everything I was looking for out of the base game.

That said, I do look forward to playing more games like Jedi Knight as we move on into a slightly more evolved era of the FPS genre as a whole. While I’m never likely to join the hardcore blood-and-guts contingent, action-packed fun like this game offers up is hard for even a reflex-challenged, violence-ambivalent old man like me to resist.

Epilogue: The Universe Shrinks

Students of history like to say that every golden age carries within it the seeds of its demise. That rings especially true when it comes to the heyday of the Expanded Universe: the very popularity of the many new Star Wars novels, comics, and games reportedly did much to convince George Lucas that it might be worth returning to Star Wars himself. And because Lucas was one of the entertainment world’s more noted control freaks, such a return could bode no good for this giddy era of fan ownership.

We can pin the beginning of the end down to a precise date: November 1, 1994, the day on which George Lucas sat down to start writing the scripts for what would become the Star Wars prequels, going so far as to bring in a film crew to commemorate the occasion. “I have beautiful pristine yellow tablets,” he told the camera proudly, waving a stack of empty notebooks in front of its lens. “A nice fresh box of pencils. All I need is an idea.” Four and a half years later, The Phantom Menace would reach theaters, inaugurating for better or for worse — mostly for the latter, many fans would come to believe — the next era of Star Wars as a media phenomenon.

Critics and fans have posited many theories as to why the prequel trilogy turned out to be so dreary, drearier even than clichés about lightning in a bottle and not being able to go home again would lead one to expect. One good reason was the absence in the editing box of Marcia Lucas, whose ability to trim the fat from her ex-husband’s bloated, overly verbose story lines was as sorely missed as her deft way with character moments, the ones dismissed by George as the “dying and crying” scenes. Another was the self-serious insecurity of the middle-aged George Lucas, who wanted the populist adulation that comes from making blockbusters simultaneously with the respect of the art-house cognoscenti, who therefore decided to make the prequels a political parable about “what happens to you if you’ve got a dysfunctional government that’s corrupt and doesn’t work” instead of allowing them to be the “straightforward, wholesome, fun adventure” he had described the first Star Wars movie to be back in 1977. Suffice to say that Lucas displayed none of Timothy Zahn’s ability to touch on more complicated ideas without getting bogged down in them.

But whatever the reasons, dreary the prequels were, and their dreariness seeped into the Expanded Universe, whose fannish masterminds saw the breadth of their creative discretion steadily constricted. A financially troubled West End Games lost the license for its Star Wars tabletop RPG, the Big Bang that had gotten the universe expanding in the first place, in 1999. In 2002, the year that the second of the cinematic prequels was released, Alan Dean Foster, the author of the very first Star Wars novel from 1978, agreed to return to write another one. “It was no fun,” he remembers. The guidance he got from Lucasfilm “was guidance in the sense that you’re in a Catholic school and nuns walk by with rulers.”

And then, eventually, came the sale to Disney, which in its quest to own all of our childhoods turned Star Wars into just another tightly controlled corporate property like any of its others. The Expanded Universe was finally put out of its misery once and for all in 2014, a decade and a half past its golden age. It continues to exist today only in the form of a handful of characters, Grand Admiral Thrawn among them, who have been co-opted by Disney and integrated into the official lore.

The corporate Star Wars of these latter days can leave one longing for the moment when the first film and its iconic characters fall out of copyright and go back to the people permanently. But even if Congress is willing and the creek don’t rise, that won’t occur until 2072, a year I and presumably many of you as well may not get to see. In the meantime, we can still use the best artifacts of the early Expanded Universe as our time machines for traveling back to Star Wars‘s last age of innocent, uncalculating fun.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Rocket Jump: Quake and the Golden Age of First-Person Shooters by David L. Craddock, How Star Wars Conquered the Universe by Chris Taylor, and The Secret History of Star Wars by Michael Kaminski. Computer Gaming World of May 1995, October 1996, January 1997, December 1997, and March 1998; PC Zone of May 1997; Retro Gamer 138; Chicago Tribune of May 24 2017.

Online sources include Wes Fenlon’s Dark Forces and Jedi Knight retrospective for PC Gamer. The film George Lucas made to commemorate his first day of writing the Star Wars prequels is available on YouTube.

Jedi Knight is available for digital purchase at GOG.com. Those who want to dive deeper may also find the original and/or remastered version of Dark Forces to be of interest.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | A reworked and remastered version of Dark Forces has recently been released as of this writing; it undoubtedly eases some of the issues I’m about to describe. These comments apply only to the original version of the game. |

|---|