Coming out of 1998, the folks at Looking Glass Studios believed they had pretty good reason to feel optimistic about their future. With Thief, they had delivered not just their first profitable original game since 1995’s Flight Unlimited but their biggest single commercial success ever. They had no fewer than four more games slated for release within the next fifteen months, a positively blistering pace for them. Yes, all of said games were sequels and iterations on existing brands, but that was just the nature of the industry by now, wasn’t it? As long-running franchises like Ultima had first begun to demonstrate fifteen years ago, there was no reason you couldn’t continue to innovate under a well-known and -loved banner headline. Looking Glass closed their Austin office that had done so much to pay the bills in the past by taking on porting contracts. In the wake of Thief, they felt ready to concentrate entirely on their own games.

Then, just as they thought they had finally found their footing, the ground started to shift beneath Looking Glass once again. Less than a year and a half after the high point of Thief’s strong reviews and almost equally strong sales, Paul Neurath would be forced to shutter his studio forever.

We can date the beginning of the cascading series of difficulties that ultimately undid Looking Glass to March of 1999, when their current corporate parent decided to divest from games, which in turn meant divesting from them. Intermetrics had been on a roller-coaster ride of its own since being purchased by Michael Alexander in 1995. In 1998, the former television executive belatedly recognized the truth of what Mike Dornbrook had tried to tell him some time ago: that his dreams and schemes for turning Intermetrics into a games or multimedia studio made no sense whatsoever. He deigned to allow the company to return to its core competencies — indeed, to double-down on them. Late in the year, Intermetrics merged with Pacer InfoTec, another perennial recipient of government and military contracts. The new entity took the name of AverStar. When one looked through its collection of active endeavors — making an “Enterprise Information Portal” for the Army Chief of Staff; developing drainage-modeling software for the U.S. Geological Survey; providing “testing and quality-support services” for the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts; writing and maintaining software for the Space Shuttle and other NASA vehicles — the games of Looking Glass stood out as decidedly unlike the others. Michael Alexander and his reconstituted team of managers, most of them grizzled veterans of the Beltway military-industrial complex, saw no point in continuing to dabble in games. In the words of Looking Glass programmer Mark LeBlanc, “AverStar threw us back into the sea.”

Just as is the case with Intermetrics’s acquisition of Looking Glass barely a year and a half earlier, the precise terms under which Alexander threw his once-prized catch back have never surfaced to my knowledge. It’s clear enough, however, that Looking Glass’s immediate financial position at this juncture was not quite so dire as it had been, thanks to the success of Thief if nothing else. Still, none of the systemic problems of being a small fish in the big pond of the games industry had been solved. Their recent success notwithstanding, without a deeper-pocketed parent or partner to negotiate for them, Looking Glass was destined to have a harder time getting their games into stores and selling them on their own terms.

The next unfortunate event — unfortunate for Looking Glass, but deeply tragic for some others — came about a month later. On April 20, 1999, two deeply troubled, DOOM-loving teenagers walked into their high school in the town of Columbine, Colorado, carrying multiple firearms each, and proceeded to kill thirteen of their fellow students and teachers and wound or terrorize hundreds more before turning their guns on themselves. This act of mass murder, occurring as it did before the American public had been somewhat desensitized to such massacres by the sheer numbing power of repetition, placed the subject of violence in videogames under the mass-media spotlight in a way it hadn’t been since Joseph Lieberman’s Senate hearings of 1993. Now Lieberman, a politician with mounting presidential ambitions, was back to point the finger more accusingly than ever.

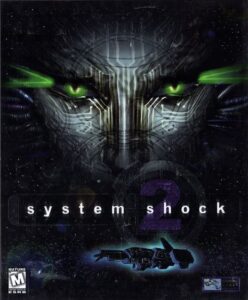

This is not the place to attempt to address the fraught subject of what actual links there might be between violence in games and violence in the real world, links which hundreds of sociological and psychological studies have never managed to conclusively prove or disprove. Suffice to say that attributing direct causality to any human behavior outside the controlled setting of a laboratory is really, really hard, even before one factors in the distortions that can arise from motivated reasoning when the subject being studied is as charged as this one. Setting all of that aside, however, this was not a form of attention to which your average gaming executive of 1999 had any wish to expose himself. First-person action games that looked even vaguely like DOOM — such as most of the games of Looking Glass — were cancelled, delayed, or de-prioritized in an effort to avoid seeming completely insensitive to tragedy. De-prioritization rather than something worse was the fate of Looking Glass’s System Shock 2, but that would prove plenty bad enough for a studio with little margin for error.

The story of System Shock 2′s creation is yet another of those “only at Looking Glass” tales. In 1994, a 27-year-old Boston-area computer consultant named Ken Levine played System Shock 1 and was bowled over by the experience. A year or so later, he saw a want ad from the maker of his favorite game in a magazine. He applied and was hired. He contributed a great deal to Thief during that project’s formative period of groping in the dark — he is credited in the finished game for “initial design and story concepts” — and then was given a plum role indeed. Looking Glass had just won a contract to make an adventure game based on the popular new television series Star Trek: Voyager, and Levine was placed in charge of it.

Alas, that project fell apart within a year or so, when Viacom, the media conglomerate that owned the property, took note of the lackluster commercial performance of another recent Star Trek adventure game — and of recent adventure games in general — and pulled the plug. Understandably enough, Levine was devastated at having thus wasted a year of his life. Somewhat less understandably, he blamed the management of Looking Glass as much as Viacom for the fiasco. He left to start his own studio, taking with him two other Looking Glass employees, by the names of Jon Chey and Rob Fermier.

This is where the story gets weird, in an oh, so Looking Glass sort of way. Once they were out on their own, trading under the name of Irrational Games, the trio found that contracts and capital were not as easy to come by as they had believed they would be. At his wit’s end, facing the prospect of a return to his former life as an ordinary computer consultant, Levine came crawling back to his old boss Paul Neurath. But rather than ask for his old job back, he asked that Irrational be allowed to make a game in partnership with Looking Glass, using the same Dark Engine that was to power Thief. Most bosses would have laughed in the face of someone who had poached two of their people in a bid to show them up and show them how it was done, only to get his comeuppance in such deserving fashion. But not Neurath. He agreed to help Levine and his friends make a game in the spirit of System Shock, Levine’s whole reason for joining the industry in the first place. In fact, he even let them move back into Looking Glass’s offices for a while in order to do it. Neurath soon succeeded in capturing the interest of Electronic Arts, the corporate parent of Origin Systems and thus the owner of the System Shock brand. Just like that, Levine’s homage became a direct sequel, an officially anointed System Shock 2.

The ironic capstone to this tale is that Warren Spector had recently left Looking Glass because he had been unable to secure permission to do exactly what the unproven and questionably loyal young Ken Levine was now going to get to do: to make a spiritual heir to System Shock. Spector ended up at Ion Storm, a new studio founded by John Romero of DOOM fame, where he set to work on what would become Deus Ex.

In the course of making System Shock 2, the Irrational staff grew to about fifteen people, who did eventually move into their own office. Nonetheless, the line separating their contributions from those of Looking Glass proper remained murky at best. As a postmortem written by Jon Chey would later put it, “the project was a collaborative effort between two companies based on a contract that only loosely defined the responsibilities of each organization.” It’s for this reason that I’ll be talking about System Shock 2 from here on like I might any other Looking Glass game.

The sequel isn’t shy about embracing its heritage. Once again, it casts you into an outer-space complex gone badly, horrifyingly haywire; this time you find yourself in humanity’s first faster-than-light starship instead of a mere space station. Once again, the game begins with you waking up disoriented, not knowing how you got here, forced to rely on narrations of the backstory that may or may not be reliable. Once again, your first and most obvious antagonists are the zombified corpses of the people who used to crew the ship. Once again, you slowly learn what really went down here through the emails and logbooks you stumble across. Once again, you have a variety of cybernetic hardware to help you stay alive, presented via a relentlessly diegetic interface. Once again, you meet SHODAN, the disembodied, deliciously evil artificial intelligence who was arguably the most memorable single aspect of the very memorable first game. And once again, she is brought to iconic life by the voice of Terri Brosius. In these ways and countless others, this apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.

But even as it embraces its heritage in the broad strokes, System Shock 2 isn’t averse to tinkering with the formula, through both subtraction and addition. The most significant edit is the elimination of a separate, embodied cyberspace, which was already beginning to feel dated in 1994, having been parachuted in straight out of William Gibson’s 1984-vintage Neuromancer. Cyberspace has its charms in System Shock 1, but few would deny that it’s the roughest part of the game in terms of implementation; it was probably a wise choice for Ken Levine and company to focus their efforts elsewhere. More debatable are their decisions to simplify the hacking mini-games that you sometimes need to play to open locked doors and the like, and to eliminate the unique multi-variant difficulty settings of the first game, which let you turn it into whatever kind of experience you desire, from a walking simulator to an exercise in non-stop carnage to a cerebral pseudo-adventure game. System Shock 2 settles for letting you choose a single setting of “Easy,” “Normal,” “Hard,” or “Impossible,” like any standard-issue shooter of the era.

In fact, at first glance this game looks very much like a standard shooter. If you try to play it as one, however, you’ll be quickly disabused of that notion when you die… and die and die and die. This isn’t a stealth game to the same extent as Thief, but it does demand that you proceed with caution, looking for ways to outwit enemies whom you can’t overcome through firepower. If you can’t see your way to noticing and disabling the security cameras that lurk in many a corner, for example, you’re going to find yourself overwhelmed, no matter how fast and accurate a trigger finger you happen to possess.

By way of a partial replacement for the multi-variant difficulty settings of its predecessor, Irrational chose to graft onto System Shock 2 more CRPG elements. Theoretically at least, these give you almost as much control over what kind of game you end up playing. You can go for a combat-oriented build if you want more of a shooter experience — within reason, that is! — or you can become a hardcore tech-head or even a sort of Jedi who makes use of “psi” powers. Or you can judiciously mix and match your abilities, as most players doubtless wind up doing. After choosing an initial slate of skills at the outset, you are given the opportunity to learn more — or to improve the ones you already have — at certain milestones in the plot.

You create your character in System Shock 2 in a similar way to the old Traveller tabletop RPG, by sending him off on three tours of duty with different service branches — or the same one, if you prefer. (I fancy I can see some traces of the Star Trek: Voyager game which Ken Levine once set out to make in the vibe and the iconography here.) This is an example of how System Shock 2 can sometimes feel like it has a few too many ideas for its own good. It seems like an awful lot of effort to go through to establish a character who is about to get his memories erased anyway.

System Shock 2 is an almost universally acclaimed game today, perhaps even more so than its uglier low-res predecessor. There are good reasons for this. The atmosphere of dread builds and builds as you explore the starship, thanks not least to masterful environmental sound design; if anything, this game is more memorable for its soundscape than for its visuals. Although its emergent qualities are certainly nothing to sneeze at, in my opinion the peak moment of the game is actually pre-scripted. A jaw-dropping plot twist arrives about halfway through, one of the most shocking I’ve ever encountered in a game. I hesitate to say much more here, but will just reveal that nothing and no one turn out to be what you thought they were, and that SHODAN is involved. Because of course she is…

For all its increased resolution and equal mastery of atmosphere, however, System Shock 2 doesn’t strike me as quite so fully realized as the first System Shock. It also suffers by comparison with Warren Spector’s own System Shock successor Deus Ex, which was released about nine months later. System Shock 2 never seems entirely sure how to balance its CRPG elements, which are dependent on character skill, with its action elements, which are dependent on player skill. Increasing your character’s skill in gunnery, for example, somehow makes your guns do more damage when you shoot someone with them; this is not exactly intuitive or realistic. Deus Ex just does so much of this sort of thing so much better. In that game, a higher skill level lets your character hold the gun steadier when you’re trying to shoot with it; this makes a lot more sense.

Unusually for Looking Glass, who seldom released a game before its time, System Shock 2 shows all the signs of having been yanked out of its creators’ hands a few months too early. The level design declines dramatically during the final third of the game, becoming downright sketchy by the time you get to the underwhelming finale. The overall balance of the gameplay systems is somewhat out of whack as well. It’s really, really hard to gain traction as a psi-focused character in particular, and dismayingly easy to end up with a character that isn’t tenable by choosing the wrong skills early on. I found a lot of the design choices in System Shock 2 to be tedious and annoying, such that I wished for a way to just turn them off: the scarcity of ammunition (another way to find yourself in an unwinnable cul de sac), the way that weapons degrade at an absurd pace and constantly need to be repaired, the endlessly respawning enemies that make hard-won firefights feel kind of pointless, the decision to arbitrarily deprive you of your trusty auto-map just at the point when you need it most.

Granted, some of this was also in System Shock 1, but it irritated me much more here. In the end, the two games provide very similar subjective experiences. Perchance this was just a ride I was only interested in going on once; perchance I would have a very different reaction to System Shock 2 if I had met it before its older sibling. Or maybe I’m just getting more protective of my time as I get older and have less and less of it left. (Ach… hold that morbid thought!)

Whatever its ratio of strengths to weaknesses, System Shock 2 didn’t do very well at all upon its release in August of 1999. Many folks from both Looking Glass and Irrational attribute this disappointment entirely to the tragic occurrence of four months earlier in Columbine, Colorado. Although the full picture is surely more nuanced — it always is, isn’t it? — we have no reason to doubt that the fallout from the massacre was a major factor in the game’s commercial failure. According to Paul Neurath, Electronic Arts pondered for a while whether it was wise to put System Shock 2 out at all. He remembers EA’s CEO Larry Probst telling him that “we may just want to walk away from doing shooters because there’s talk of these shooters causing these kinds of events.” “We convinced them to release the game,” says Neurath, “but they did almost zero marketing and they put it in the bargain discount $9.95 bin 45 days after the game launched. It never stood a chance to make any money. That really hurt us financially.”

If System Shock 2 was to some extent a victim of circumstances, Looking Glass’s next game was a more foreseeable failure. For some reason, they just couldn’t stop beating the dead horse of flight simulation, even though it had long since become clear that this wasn’t what their primary audience wanted from them at all. Flight Unlimited III wasn’t a bad flight simulator, but the changes it introduced to the formula were nowhere near as dramatic as those that marked Flight Unlimited II. The most notable new development was a shift from the San Francisco Bay to Washington State, a much larger geographical area depicted in even greater detail. (Owners of the second game were given the privilege of loading their old scenery into the new engine as well.) Innovation or the lack thereof aside, the same old problem remained, in the form of Microsoft’s 800-pound-gorilla of a flight-simulation franchise, which was ready with its own “2000” update at the same time. Published by Electronic Arts in late 1999, Flight Unlimited III stiffed even more abjectly than had System Shock 2.

On the left, we see Seattle-Tacoma International Airport as depicted in Microsoft’s Flight Simulator 2000. On the right, we see the same airport in Flight Unlimited III. The former modeled the whole world, including more than 20,000 airports; the latter tried to compete by modeling a comparatively small area better. Regardless of the intrinsic merits of the two approaches, Looking Glass’s did not prove a formula for marketplace success.

A comparatively bright spot that holiday season was Thief Gold, which added three new missions to the original’s twelve and tweaked and polished the existing ones. It did decently well as a mid-tier product with a street price of about $25, plus a $10 rebate for owners of the previous version of Thief and the promise of a $10 discount off the upcoming Thief II. But a product like this was never going to offset Looking Glass’s two big failures of 1999.

In truth, the Looking Glass goose was probably already more or less cooked as Y2K began. The only thing that might have saved them was Thief II: The Metal Age turning into a massive hit right out of the gate. Sadly, there was little likelihood of that happening; the best that Looking Glass could realistically hope for was another solid half-million seller. There was already a sense in the studio as the final touches were being put on Thief II that, barring a miracle, this game was likely to be their swansong.

As swansongs go, Thief II acquits itself pretty darn well. It comes off as far more self-assured than its predecessor, being focused almost exclusively on stealth rather than monster-slaying through its fifteen cunningly crafted levels. Some of these spaces — a huge central bank, a sprawling warehouse complex, a rich art collector’s country estate — are intricate and beautiful enough that you almost wish there was an option to just wander around and admire them, without having to worry about guards and traps and all the rest. There’s a greater willingness here to use gameplay to advance the larger story: plot twists sometimes arrive in the midst of a mission, and you can often learn more about what’s really going on, if you’re interested, by listening carefully to the conversations that drift around the outskirts of the darkness in which you cloak yourself. Indeed, Thief II is positively bursting with little Easter eggs for the observant. Some of them are even funny, such as a sad-sack pair of guards who have by now been victimized by Garrett several times in other places, who complain to one another, Laurel and Hardy style, about their lot in life of constantly being outsmarted.

The subtitle pays tribute to the fact that the milieu of Thief has now taken on a distinct steampunk edge, with clanking iron robots and gun turrets for Garrett to contend with in addition to the ever-present human guards. Garrett now has a mechanical eye which he can use to zoom in on things, or even to receive the visual signal from a “scouting orb” that he’s tossed out into an exposed space to get a better picture of his surroundings. I must confess that I’m somewhat of two minds about this stuff: it’s certainly more interesting than zombies, but I do still kind of long for the purist neo-Renaissance milieu I thought I was getting when I played the first level of Thief I.

The “faces” on the robots look a bit like SHODAN, don’t they? Some of the code governing their behavior was also lifted directly from that game. But unlike your mechanical enemies in System Shock 2, these robots have steam boilers on their posteriors which you can douse with water arrows to disable them.

Beyond this highly debatable point, though, there’s very little to complain about here, unless it be that Thief II, for all its manifest strengths, doesn’t quite manage to stand on its own. Oddly in light of what a make-or-break title this was for them, Looking Glass seems not to have given much thought to easing new players into this very different way of approaching a first-person action game; they didn’t even bother to rehash the rudimentary tutorial that kicks off Thief I. As a result, and as a number of otherwise positively disposed contemporary reviewers noted, Thief II has more the flavor of an expansion pack — a really, really well-done one, mind you — than a full-fledged sequel. It probably isn’t the best place to start, but anyone who enjoyed the first game will definitely enjoy this one.

Looking Glass’s problem, of course, was that none of what I’ve just written sounds like a ticket to id- or Blizzard-level success, which was what they needed by this point to save the company. As Computer Gaming World wrote in its review, Thief II “is a ’boutique’ game: a gamer’s game. It pays its dividends in persistent tension rather than in bursts of fear. It still pumps as much adrenaline, but it works on a subtler level. It’s the difference between Strangers on a Train and Armageddon, between the intimated and the explicit.”

Having thus delivered another cult classic rather than a blockbuster, Looking Glass’s fate was sealed. By March of 2000, when Eidos published Thief II, Paul Neurath had been trying to sell the studio for a second time for the better part of a year. Sony was seriously interested for a while, until a management shakeup there killed the deal. Then Eidos was on the verge of pulling the trigger, only to have its bankers refuse to loan the necessary funds after a rather disappointing year for the company, in which the Tomb Raider train seemed to finally be running out of steam and John Romero’s would-be magnum opus Daikatana, which Eidos was funding and publishing for Ion Storm, ran way over time and budget. Not wanting to risk depriving his employees of their last paychecks, Neurath decided to shut the studio down with dignity. On May 24, 2000, he called everyone together to thank them for their efforts and to tell them that Thief II had been Looking Glass’s last game. “We’re closing,” he said. What else was there to say?

Plenty, as it turned out. The news of the shuttering prompted paroxysms of grief throughout gaming’s burgeoning online ecosystem, frequently accompanied by a full measure of self-loathing. Looking Glass had been just too smart for a public that wasn’t worthy of them, so the story went. Many a gamer who had always meant to pick up this or that subtly subversive Looking Glass masterstroke, but had kept delaying in favor of easier, more straightforward fare, blamed himself for being a part of the problem. But no amount of hand-wringing or self-flagellation could change the fact that Looking Glass was no more. The most it could do was to turn having worked for the studio into a badge of honor and one hell of a line item on anyone’s CV, as a Looking Glass diaspora spread out across the industry to influence its future.

To wit: the tearful tributes were still pouring in when Ion Storm’s Warren Spector-led Deus Ex reached store shelves in June of 2000. Cruel irony of ironies: Deus Ex became a hit on a scale that Thief, Looking Glass’s biggest game ever, could scarcely have dreamed of approaching. Right to the end, Looking Glass was always the bridesmaid, never the bride.

Looking Glass was a cool group, and a lot of us put a lot of time and energy and a large part of our lives into it, and it’s sad when that doesn’t work out. So there’s some part of me that says, oh, that sucks, that’s not fair, but it’s the real world and it had a pretty good run.

— Doug Church

Without consciously intending to, I’ve found myself writing quite a lot of obituaries of gaming icons recently: TSR, Sierra On-Line, MicroProse, Bullfrog, the adventure-making arm of Legend Entertainment. Call it a sign of the millennial times, a period of constant, churning acquisition and consolidation in which it began to seem that just half a dozen or so many-tendriled conglomerates were destined to divide the entirety of digital gaming among themselves. Now, we can add Looking Glass to our list of victims of this dubious idea of progress.

A lot of hyperbole has been thrown around about Looking Glass over the past quarter-century. A goodly portion of it is amply justified. That said, I do think there is some room for additional nuance. (There always is, isn’t there?) At the risk of coming off like the soulless curmudgeon in the room, I’m not going to write about Looking Glass here as if they were a bunch of tortured artists starving in a garret somewhere. Instead I’m going to put on my pragmatist’s hat and go off on in search of some more concrete reasons why these remarkable games didn’t resonate as much as they may have deserved to back in the day.

It shouldn’t be overlooked that Paul Neurath and Ned Lerner made some fairly baffling business decisions over the years. Their disastrous choice to try to make a go of it as an independent publisher against gale-force headwinds in 1995 can be all too easily seen as the precipitating event that sent Looking Glass down the road to closure five years later. Then, too, Neurath’s later insistence on persisting with the Flight Unlimited series must stand high on the list of mistakes. Incredibly, at the time Looking Glass was shut down, they were still at the flight-simulation thing, having spent a reported $3 million already on a fourth one, which was finally to add guns and enemy aircraft to the mix; this was half a million more than they had spent to make Thief II, a game with a far more secure customer base.

Then again, this isn’t a Harvard Business School case study. What final words are there to say about the games themselves, the real legacy of this company that failed rather spectacularly at its business-school ambition of making a lot of — okay, any — money? How should we understand them in their full historical context?

As you probably know, historical context is kind of my jam. Writing for this site is for me a form of time travel. I don’t play modern games for lack of hours in the day, and I’ve long since settled into a more or less one-to-one correspondence between present time and historical time; that’s to say, it takes me about one year worth of articles on this site to fully cover one year of gaming history and matters adjacent. We’ve by now moved out of the era when I was playing a lot of games in my previous life, so most of what I encounter is new to me. I think this puts me in a privileged position. I can come pretty close to experiencing and appreciating games — and the evolution of the medium as a whole — as a contemporary player might have done. When I read in the year 2025 that Looking Glass was poorly rewarded for their uncompromising spirit of innovation, I can understand and even to a large extent agree. And yet, in my role as a time traveler, I can also kind of understand why a lot of gamers ended up voting with their wallets for something else.

The decade after Looking Glass’s demise saw the rise of what gaming scholar Jesper Juul has dubbed the Casual Revolution; this was the heyday of Bejeweled, Zuma, Diner Dash, and the Big Fish portal, which brought gaming to whole new, previously untapped demographics who dwarfed the hardcore old guard in numbers. In 2010, when this revolution was at its peak, Juul put forth five characteristics that define casual gaming: “emotionally positive fictions”; “little presupposed knowledge” on the player’s part; a tolerance for being played in “short bursts”; “lenient punishments for failing”; and “positive feedback for every successful action the player performs.” The games of Looking Glass are the polar opposite of this list. At times, they seem almost defiantly so; witness the lack of an “easy” setting in Thief, as if to emphasize that anyone who might wish for such a thing is not welcome here. Looking Glass’s games are the ultimate “gamer’s games,” as Computer Gaming World put it, unabashedly demanding a serious commitment of time, focus, energy, and effort from their players. But daily life demands plenty of those things from most of us already, doesn’t it? In this light, it doesn’t really surprise me that a lot of people decided to just go play something more welcoming and less demanding. This didn’t make them ingrates; it just made them people who weren’t quite sure that there was enough space in their life to work that hard for their entertainment. I sympathize because I often felt the same in the course of my time-traveling; when I saw a new Looking Glass game on the syllabus, it was always a little bit harder than it ought to have been for me to muster the motivation to take the plunge. And this is part of what I do for a living!

Now, there’s certainly nothing wrong with gamer’s games. But they are by definition niche pursuits. The tragedy of Looking Glass (if I can presume to frame it in those terms in an article which has previously mentioned the real tragedy that took place at Columbine High School) is that they were making niche games at a time when the economics of the industry were militating against the long tail, pushing everyone toward a handful of tried-and-true mainstream gameplay formulas. After the millennium, the rise of digital distribution would give studios the luxury of being loudly and proudly niche, if that was where their hearts were. (Ironically, this happened at the same instant that ultra-mainstream casual gaming took off, and was enabled by the same transformative technology of broadband in the home.) But digital distribution of games as asset-heavy as those of Looking Glass was a non-starter throughout the 1990s. C’est la vie.

This situation being what it was, I do feel that Looking Glass could have made a bit more of an effort to be accessible, to provide those real or metaphorical easy modes, if only in the hope and expectation that their customers would eventually want to lose the training wheels and play the games as they were meant to be played. On-ramping is a vital part of the game designer’s craft, one at which Looking Glass, for all their strengths in other areas, wasn’t all that accomplished.

Another thing that Looking Glass was not at all good at, or seemingly even all that interested in, was multiplayer, which became a bigger and bigger part of gaming culture as the 1990s wore on. (They did add a co-operative multiplayer mode to System Shock 2 via a patch, but it always felt like the afterthought it was.) This was a problem in itself. Just to compound it, Looking Glass’s games were in some ways the most single-player games of them all. “Immersion” was their watchword: they played best in a darkened room with headphones on, almost requiring of their players that they deliberately isolate themselves from the real world and its inhabitants. Again, this is a perfectly valid design choice, but it’s an inherently niche one.

Speaking only for myself now, I think this is another reason that the games of Looking Glass proved a struggle for me at times. At this point in my life at least, I’m just not that excited about isolating myself inside hermetically sealed digital spaces. If I want total immersion, I take a walk and immerse myself in nature. Games I prefer to play on the sofa next to my wife. My favorite Looking Glass game, for what it’s worth, is System Shock 1, which I played at an earlier time in my life when immersion was perhaps more of a draw than it is today. Historical context is one thing, personal context another: it’s damnably difficult to separate our judgments of games from the circumstances in which we played them.

Of course, this is one of the reasons that I always encourage you not to take my judgments as the final word on anything, to check out the games I write about for yourself if they sound remotely interesting. It’s actually not that hard to get a handle on Looking Glass’s legacy for yourself. Considering the aura of near-divinity that cloaks the studio today, the canon of widely remembered Looking Glass classics is surprisingly small. They seem to have had a thing for duologies: their place in history boils down to the two Ultima Underworld games, the two System Shock games, and the two Thief games. The rest of their output has been pretty much forgotten, with the partial exception of Terra Nova on the part of the really dedicated.

Still, three bold and groundbreaking concepts that each found ways to advance the medium on multiple fronts is more than enough of a legacy for any studio, isn’t it? So, let us wave a fondly respectful farewell to Looking Glass, satisfied as we do so that we will be meeting many of their innovations and approaches, sometimes presented in more accessible packages, again and again as we continue to travel through time.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, please think about pitching in to help me make many more like it. You can pledge any amount you like.

Sources: The books Game Design Theory & Practice (2nd. ed.) by Richard Rouse III, A Casual Revolution: Reinventing Video Games and Their Players by Jesper Juul, and the Prima strategy guide to Thief II by Howard A. Jones; Computer Gaming World of January 1999, November 1999, January 2000, February 2000, and June 2000; Retro Gamer 60, 177, and 260; Game Developer of November 1999; Boston Globe of May 26 2000; Boston Magazine of December 2013.

Online sources include “Ahead of Its Time: A History of Looking Glass” and “Without Looking Glass, There was No Irrational Games” by Mike Mahardy at Polygon, James Sterrett’s “Reasons for the Fall: A Post-Mortem on Looking Glass Studios,” a GameSpy featurette by John “Warrior” Keefer, Christian Nutt’s interview with Ken Levine on the old Gamasutra site, and AverStar’s millennial-era corporate site.

My special thanks to Ethan Johnson, a fellow gaming historian who knows a lot more about Looking Glass than I do, and set me straight on some important points after the first edition of this article was published.

Where to Get Them: System Shock 2: 25th Anniversary Remaster (which includes the original version of the game as a bonus) and Thief II: The Metal Age are available as digital purchases on GOG.com.