On Wednesday, in the small Palestinian shepherding village of Mukhmas, a masked Jewish settler armed with an M16 shot and killed a 19-year-old Philadelphia native named Nasrallah Abu Siyam. It’s highly likely that the gun was supplied by the United States. At least four other local Palestinians were wounded by settler gunfire during the invasion of the village, including another young man whose foot may be amputated. Some were shot while carrying the wounded to safety. Many others were severely beaten with metal rods. Israeli soldiers, who accompanied the settlers into the village, responded to the shooting rampage by firing stun grenades and tear gas into the residential area, burning an elderly man. When it was over, settlers walked off with more than 300 of the village’s sheep and goats under the military’s watch. It was the first full day of Ramadan. As of this writing, no one has been arrested.

Two days after the attack, I spoke with eight young men who had been there, several of them injured, some among those who carried Nasrallah to a car and drove him toward the hospital. Teenagers and men in their early twenties. At least one of them had braces—Nasrallah had them, too. Not hardened fighters; students, farmers, and shepherds. They looked exhausted. A few had fresh wounds on their faces. They startled at sudden noises, repeatedly springing up to peer out the window. I am protecting their identities, as retaliation in cases like these is common.

In all likelihood, no one will be held accountable for this killing, but it is important to bear witness and to leave a record of what happened. What follows is a reconstruction based on the account of these eight witnesses. To be clear, I did not obtain the settlers’ version of events, though if I had their contact information, I certainly would have tried. The IDF did not respond to my request for comment. The testimony presented here is consistent with reporting in major Israeli and Palestinian outlets, available video evidence, the patterns of state and settler violence that shape daily life in the West Bank, and my own experience there over the past several years.

Before turning to their account, I want to situate what happened within the broader system that produced it. Late last year, I wrote two pieces unpacking Israel’s machinery of annexation in its current form, based in part on an op-ed from a settler leader and unusually candid testimony from within the Israeli military. The picture that emerged was of a system in which settler leaders and military officers work in close collaboration to map target areas for land seizure and establish illegal outposts under army protection, from which settlers launch pogroms on vulnerable Palestinian communities, often with military escorts, in an effort to terrorize them into leaving.

Sometimes that pressure alone is enough—over 80 rural Palestinian communities have been abandoned since October 7. Other times, the military declares a “closed military zone,” clearing Palestinians from their land under the pretense of preventing further violence. In some cases, settlers provoke a confrontation that is then used to justify further military action. One way or another, the relentless settler attacks function as the spearhead of a state policy of ethnic cleansing, with the government managing the aftermath and absorbing the gains. Through this process, vast stretches of Area C—where Israel exercises full control—have been emptied of Palestinians, while settler incursions are increasingly pushing into Areas B and even A, nominally controlled by the Palestinian Authority.

The broader vision, articulated openly by settler leaders and their allies in government, is to force Palestinians to emigrate, and to concentrate those who remain into a handful of urban enclaves—Jenin, Tulkarm, Nablus, Ramallah, Jericho, and Hebron—while annexing the rest of the territory. “The principle of sovereignty is maximum land and minimum population,” Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich said while outlining the plan.

There is another angle to this story—that yet another American citizen has been killed by Israelis, with no expectation that anyone will be held accountable—but I’m going to leave that for another time. For now, I will say only that I learned of the killing from Kamel Musallet, the father of Sayfollah Musallet, who was beaten to death by settlers in July.

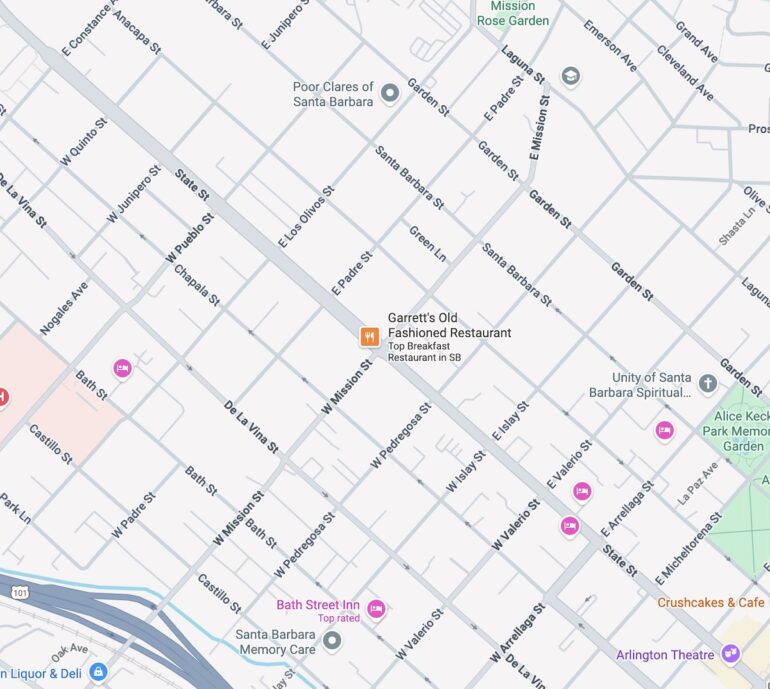

For generations, a Bedouin encampment known as Khallat al-Sidra—a cluster of tents, cinderblock shelters, and animal pens—sat on the edge of Mukhmas. The land belonged to the village, but a mayor many decades earlier had invited the Bedouins to settle there, to plant olive trees and graze their livestock. Over the years, the community also served as an incidental buffer between the village of Mukhmas and the most violent settlers descending from the hills. While Mukhmas residents were regularly attacked in their fields, they were typically safe in the village itself, as Khallat al-Sidra absorbed the worst of the attacks. In part, this was a matter of basic geography. But the Bedouin encampment and surrounding farmland also lay in Area C, making them far more vulnerable to settler violence than the built-up village of Mukhmas, which sits in Area B.

When settlers raided Khallat al-Sidra, Mukhmas residents often came down to help protect them, but after October 7, that became nearly impossible. A new ring of outposts went up around the area, and the settlers’ proximity allowed them to strike fast, often in the dead of night, launching attacks before the village could even be roused.

In a period of just over three months between late October and late January, settlers descended on Khallat al-Sidra and torched homes on three separate occasions. Each time, the community rebuilt, only to see it burned again. I was present the morning after one of these pogroms, and toured the charred structures with men and their traumatized children as settlers circled us on their ATVs, many with machine guns slung over their shoulders. Two activists had been sent to the hospital.

In a January attack on Khallat al-Sidra captured on video, the settlers split into groups, moving methodically from structure to structure, burning the whole village to the ground in minutes. Settlers blocked a man and a woman from escaping from their burning home, beating them when they finally escaped. Videos circulating on far-right social media celebrated the pogrom, set to the beloved settler anthem, May Your Village Burn.

After the most recent attack in late January, the Israeli military, rather than arrest the settlers responsible and evacuate their outposts, declared the area a closed military zone and forcibly expelled the Bedouin community. This was, of course, a tragedy in its own right. It also meant the frontier shifted overnight—from Khallat al-Sidra in Area C to Mukhmas in Area B—exposing the village to the same tactics used to clear the surrounding hills.

On Wednesday at 2:35 pm, a shepherd from Mukhmas, grazing his sheep and goats in the village’s farmland, was surrounded by settlers who harassed him and attempted to steal his livestock. He managed to escape with his flock and ran back toward the village, just outside the girls’ school, where a group of local men gathered to form a defensive barrier. Many of the settlers wore masks, but the villagers recognized several from previous attacks. Among them was a settler named Amir, a security guard for one of the nearby outposts. He claimed he was there to help, firing his M16 into the air and ordering Mukhmas’s residents to retreat, promising he would escort the settlers away without incident. The villagers knew that if they withdrew, their livestock would be taken.

Minutes later, more settlers arrived, accompanied by soldiers—the same platoon, villagers said, that routinely appears during these incursions, likely assigned to this particular settler gang by the IDF’s Central Command. Now there were roughly 30 settlers and five soldiers at the edge of Mukhmas. The troops joined Amir in ordering the Palestinian men back into the village, assuring them the animals would not be touched. But as soon as the villagers began to withdraw, settlers opened the enclosure and started driving the livestock out.

At 3:27 pm, the first physical violence broke out as several Palestinian men moved to retrieve their livestock and were beaten back by settlers and soldiers. Troops fired tear gas and stun grenades into the village; an elderly man was badly burned by a canister. In footage from the incident, women and children can be heard screaming from inside their homes. Settlers pushed deeper into the residential area in the chaos, opening additional enclosures and driving off more sheep and goats.

A group of villagers broke off and took a back route, hoping to intercept the settlers driving off their animals—their primary livelihood. One of the men was seized and surrounded, settlers beating him with metal rods as he lay unconscious on the ground. Others rushed forward to attempt to pull him free. The settlers hurled stones to drive them back, and the villagers threw stones in return.

At 3:48 pm, a settler raised his M16 and began firing into the crowd rushing toward their wounded fellow villager. Four or five others followed suit, gunning down the Palestinians on their own land. Five men were hit, including the brother of the wounded man. Nasrallah was shot in the thigh, the bullet severing his main artery. Settlers crowded around him after he fell, striking him with rods. At least one of the gunmen dropped to a knee in a military firing position, taking deliberate aim at those carrying the injured to safety. As the shooting unfolded, the army, just down the hill, continued gassing the village.

When the shooting ended, the army did not stick around to provide medical assistance to the men lying wounded with gunshot injuries. Instead, they withdrew from Mukhmas alongside the settlers, who walked off with more than 300 of the village’s sheep and goats—a crippling economic blow to three shepherding families.

The villagers called an ambulance, but it couldn’t get past a nearby army checkpoint, so they loaded the wounded into several cars and began driving toward the hospital in Ramallah. Traffic was gridlocked near the checkpoint, and as word spread, other drivers tried to clear a path, waving vehicles aside and shouting for space. Nasrallah was bleeding heavily in the back seat, his pulse fading. When the cars could move no further, the men lifted him out and carried him on foot toward a waiting ambulance on the other side. By the time he reached the hospital at 5:30 pm, nearly two hours had passed since he was shot.

For four and a half hours, doctors attempted to save his life. But he had lost too much blood. At 10 pm, 19-year-old Nasrallah Abu Siyam was pronounced dead.

Later that night, settlers returned to Mukhmas, revving their engines and shining lights into homes. The men came out again to protect their village, this time in even larger numbers, and the settlers left without incident.

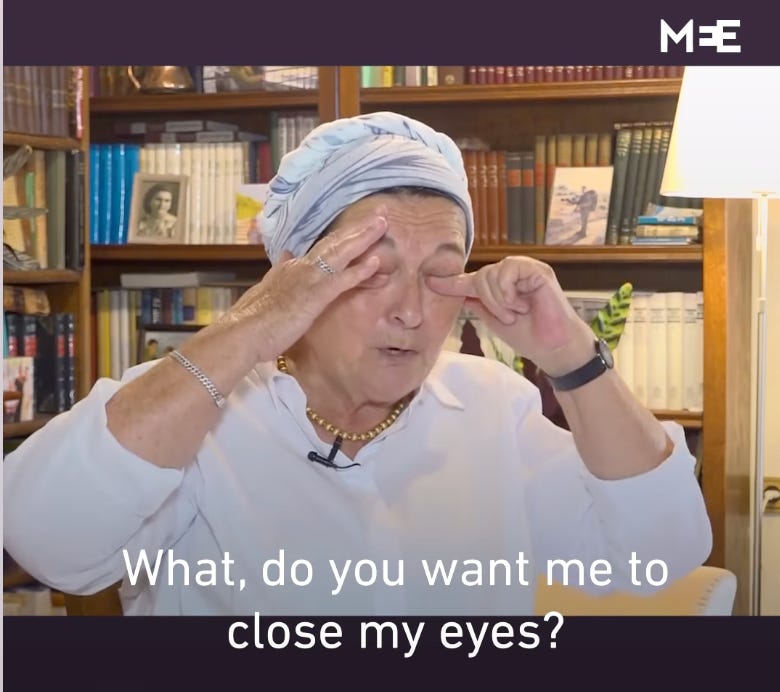

When I returned home from the West Bank after last year’s olive harvest, I found it difficult to articulate the feeling of sheer terror in Palestinian villages subjected to regular settler attacks, where I spent many sleepless nights. There is nothing quite like the real fear of physical danger, knowing it can arrive at any moment, and that you are completely defenseless. (In communities across the West Bank, residents know that if they take up arms to defend themselves, their village may be wiped from the map—as has happened in Jenin and Tulkarm, long associated with militant activity.) I, of course, could leave whenever I chose; for the Palestinians, this is daily life.

I can only imagine it as something akin to the atmosphere Black families described in parts of the Jim Crow South, where the Ku Klux Klan rode at night, the law often on their side, delivering warnings in fire and blood. Lynchings were staged to strike maximum fear into the hearts of entire communities—to enforce racial hierarchy, crush political participation, and drive families from land and livelihoods they had built. The message was unmistakable: you have no protection here, and whatever you have can be taken.

Today, in the West Bank, giant Stars of David jut from the ground, lit at night like flaming crosses. The assailants often arrive with military-grade assault rifles capable of ending a life in an instant. Again, I am lost for words trying to describe the feeling of a belligerent teenager aiming one of these death machines right at you. They operate not with tacit protection from the law, as the KKK did, but with the visible backing of soldiers and a state apparatus whose purpose, in practice and in stated policy, is to assert dominance over every aspect of daily life. To make you disappear.

Many of the most violent settlers and their leaders are well known to local Palestinians, activists, journalists, and Israeli authorities alike. Several participants in the Mukhmas attack have already been identified by activists, and I have previously written about the settler leader Amishav Melet, whom I believe orchestrated the Turmus’ayya assault I documented in October. If major news organizations devoted to this historic campaign of violence the same investigative resources they apply to other conflicts, I have no doubt they could map the settler terror infrastructure and chain of command much as they do clandestine militant groups elsewhere. Israeli authorities almost certainly possess such intelligence already, but the pattern suggests it is used to manage and protect these networks rather than dismantle them.

In other words, the Israeli reign of terror in the West Bank is not an inevitable force of nature. It can be stopped. Allowing it to continue is a series of choices—by the Israeli government, by its backers in Washington, and, more tacitly, by a mainstream media ecosystem that largely treats it as a peripheral regional conflict, surfacing only when the violence becomes too graphic or politically destabilizing to ignore.

On Saturday, the U.S. State Department broke its silence, failing to condemn the killing or mention the assailants: “We can confirm the death of a U.S. citizen in the West Bank on February 18. We extend our deepest condolences to the family and expect a full, thorough, and transparent investigation into the circumstances surrounding the death. U.S. Embassy Jerusalem has been in direct contact with the family to provide assistance.”

Ambassador Mike Huckabee, for his own part, has been in crisis mode—though for different reasons—firing off 31 tweets in two days defending his calamitous interview with Tucker Carlson, during which he asserted Israel’s biblical right to claim all the land between the Nile and the Euphrates, triggering a diplomatic crisis.

Nasrallah Abu Siyam is at least the seventh American killed by Israeli settlers or soldiers in the West Bank since October 7. No one has been arrested in any of the cases. No one has been held accountable.

If you’d like to support farmers in the West Bank, consider donating to Roots of Resilience.