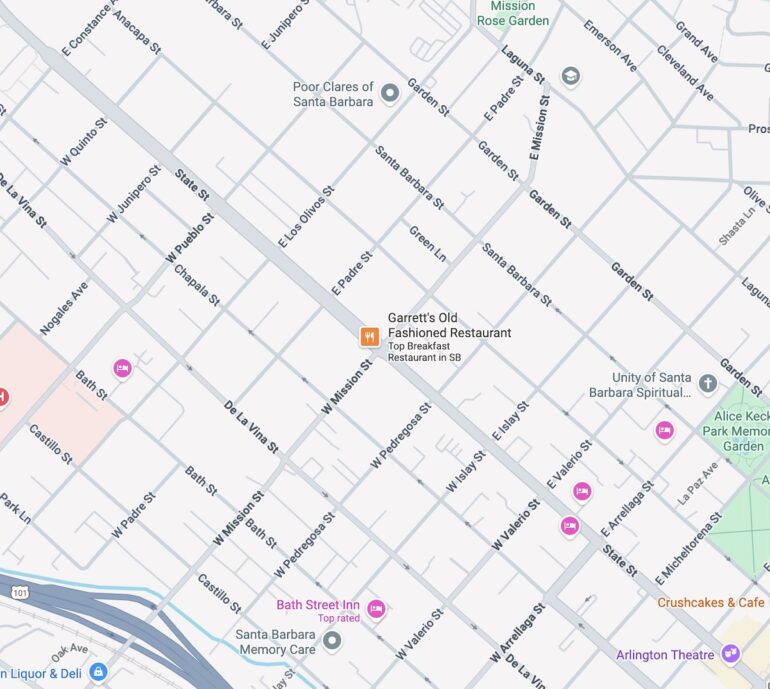

The 12 blocks of State Street between Sola Street and Constance Avenue are remarkably diverse, which may be why no specific visual pops up when I think of the “Mid-State” area. Another factor is that I rarely ever walk more than one block at a time; it’s a part of town where you’re more likely to drive directly to your destination.

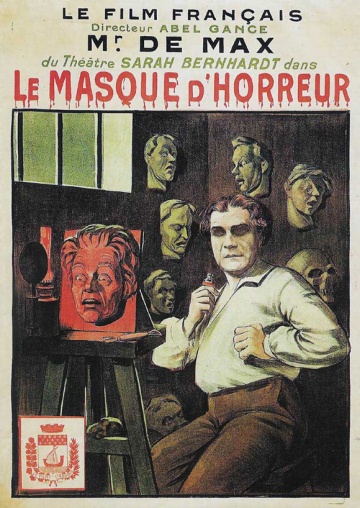

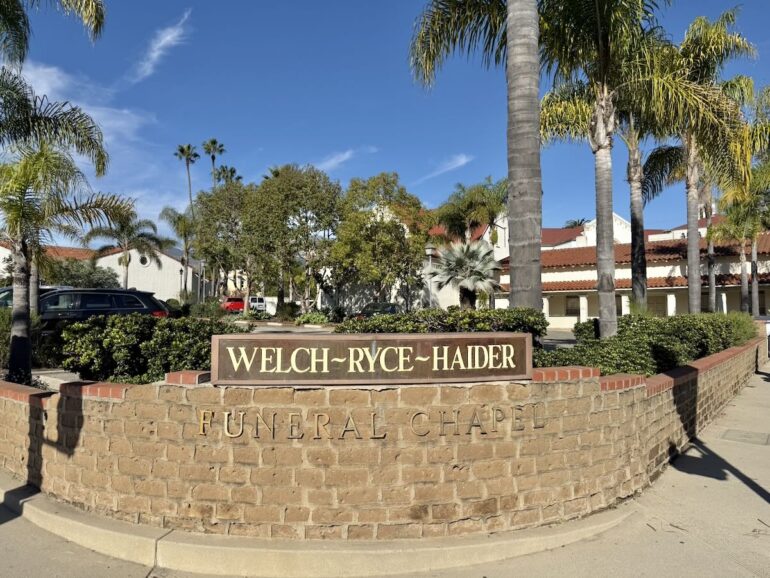

Starting at Sola, I headed up the east side of State and down the west. One point of differentiation from lower State Street quickly became clear: the open space—mainly for parking lots and gardens—makes the area feel less dense, and therefore less urban. Moreover, the placement of parking lots at the street, rather than behind buildings, pushes the atmosphere in a suburban direction. Take the Welch-Ryce-Haider funeral home (named for three individuals, as we learned during the Arts District walk), and the U.S. Bankruptcy Court.

Starting at Sola, I headed up the east side of State and down the west. One point of differentiation from lower State Street quickly became clear: the open space—mainly for parking lots and gardens—makes the area feel less dense, and therefore less urban. Moreover, the placement of parking lots at the street, rather than behind buildings, pushes the atmosphere in a suburban direction. Take the Welch-Ryce-Haider funeral home (named for three individuals, as we learned during the Arts District walk), and the U.S. Bankruptcy Court.

The suburban feel kicks up a notch at the Community West Bank and IHOP. In a city desperate for housing, downtown properties like these seem so ripe for redevelopment.

The handsome Trinity Episcopal Church took me back to my college days at Duke—because of the Gothic architecture, and also because it essentially has a quad to the north.

The handsome Trinity Episcopal Church took me back to my college days at Duke—because of the Gothic architecture, and also because it essentially has a quad to the north.

The huge garden at 1436 State Street, home to a Village Properties office, would make a lovely public plaza. The shield shape on the facade has me thinking that the building might have been a financial institution at one time.

The huge garden at 1436 State Street, home to a Village Properties office, would make a lovely public plaza. The shield shape on the facade has me thinking that the building might have been a financial institution at one time.

The open space is occasionally in the middle of a lot, as is the case with the Orange Tree Inn and Presidio Motel.

The open space is occasionally in the middle of a lot, as is the case with the Orange Tree Inn and Presidio Motel.

Speaking of hotels, every now and then inquiring minds ask me why the Mission Inn, between Islay and Pedregosa, is taking so long. It certainly is a maximalist affair, even more remarkable when you consider the location overlooking a gas station. Someone on site recently told me that the rooms are basically finished, and the hotel should be open in six months or so. I’m still hoping for a tour.

Speaking of hotels, every now and then inquiring minds ask me why the Mission Inn, between Islay and Pedregosa, is taking so long. It certainly is a maximalist affair, even more remarkable when you consider the location overlooking a gas station. Someone on site recently told me that the rooms are basically finished, and the hotel should be open in six months or so. I’m still hoping for a tour.

The back of the hotel is less frosted. Don’t let the entreaty to “shake hands with beef”—er, pass—distract you from the trio of side-by-side doors.

The back of the hotel is less frosted. Don’t let the entreaty to “shake hands with beef”—er, pass—distract you from the trio of side-by-side doors.

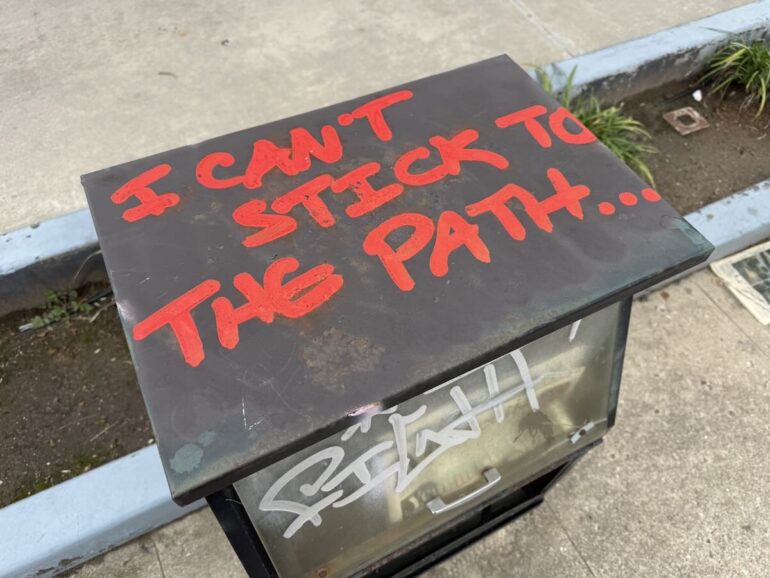

Another work by the same artist/poet.

Another work by the same artist/poet.

The Courtyard by Marriott Santa Barbara Downtown—a name optimized for search engines, not mouthfeel—does indeed have a courtyard with a pool, as well as an expansive rooftop terrace.

The Courtyard by Marriott Santa Barbara Downtown—a name optimized for search engines, not mouthfeel—does indeed have a courtyard with a pool, as well as an expansive rooftop terrace.

The weirdest hostelry? The short-term rentals at 1524 State Street. Being in a unit toward the back wouldn’t be so bad, but the room right on State is another story. In a perfect world, these would be apartments, but given the way city politicians treat landlords, one can hardly blame developers for choosing hotels over housing.

The weirdest hostelry? The short-term rentals at 1524 State Street. Being in a unit toward the back wouldn’t be so bad, but the room right on State is another story. In a perfect world, these would be apartments, but given the way city politicians treat landlords, one can hardly blame developers for choosing hotels over housing.

Another distinguishing characteristic of the area: houses, often converted to commercial use. The single-story buildings are especially charming when a paseo threads through or between them.

Another distinguishing characteristic of the area: houses, often converted to commercial use. The single-story buildings are especially charming when a paseo threads through or between them.

I love the L.M. Caldwell building at 1509 State. It was a pharmacy; the Independent and Noozhawk covered the business’s 2017 closing in starkly different ways.

I love the L.M. Caldwell building at 1509 State. It was a pharmacy; the Independent and Noozhawk covered the business’s 2017 closing in starkly different ways.

Bigger buildings hog the spotlight, of course. There are some doozies, like the aforementioned U.S. Bankruptcy Court and 1722 State (below), which could pass for a Masonic Temple and brings up three thoughts: 1) The freestanding arch in front is a fascinating folly—it reminds me of a small fish being eaten by a big one; 2) the use of “arts” in regard to medicine always makes me a little nervous—I like my science straight up—but it’s more apt in this case (plastic surgery); and 3) the bench on the south side of the building sure is a pleasant spot to ponder the mechanicals.

Bigger buildings hog the spotlight, of course. There are some doozies, like the aforementioned U.S. Bankruptcy Court and 1722 State (below), which could pass for a Masonic Temple and brings up three thoughts: 1) The freestanding arch in front is a fascinating folly—it reminds me of a small fish being eaten by a big one; 2) the use of “arts” in regard to medicine always makes me a little nervous—I like my science straight up—but it’s more apt in this case (plastic surgery); and 3) the bench on the south side of the building sure is a pleasant spot to ponder the mechanicals.

PayJunction‘s headquarters at 1903 State is also a mishmash, with vestigial doorways. Was it once an inn? Or another funeral home? (If you were wondering, “The PayJunction platform simplifies the integration of payment processing for developers and businesses, enabling them to accept payments with no-code.” Cleared it right up, eh?)

PayJunction‘s headquarters at 1903 State is also a mishmash, with vestigial doorways. Was it once an inn? Or another funeral home? (If you were wondering, “The PayJunction platform simplifies the integration of payment processing for developers and businesses, enabling them to accept payments with no-code.” Cleared it right up, eh?)

Last I heard, in early 2023, the midcentury building at 1919 State, along with its neighbors at 1913 and 1921 State, is being converted into a 73-room self-service hotel (i.e., any staff is not necessarily on site and reachable via text). It’s another lot that could’ve/should’ve been housing—and maybe even would’ve been housing, if the city made the prospect more appealing.

Last I heard, in early 2023, the midcentury building at 1919 State, along with its neighbors at 1913 and 1921 State, is being converted into a 73-room self-service hotel (i.e., any staff is not necessarily on site and reachable via text). It’s another lot that could’ve/should’ve been housing—and maybe even would’ve been housing, if the city made the prospect more appealing.

One one hand, 1704 State earns credit for putting the parking lot in back. On the other hand, the corner (Valerio) got short shrift. Corners are an opportunity! They deserve better than a maintenance closet.

One one hand, 1704 State earns credit for putting the parking lot in back. On the other hand, the corner (Valerio) got short shrift. Corners are an opportunity! They deserve better than a maintenance closet.

And let’s put some effort into that devil’s strip.

And let’s put some effort into that devil’s strip.

Attention must be paid to the building’s extreme cornice and massive sconces.

Attention must be paid to the building’s extreme cornice and massive sconces.

Buildings, buildings, buildings…. There were so many to ponder that I must’ve gotten a little bleary because I didn’t notice the sculpture adorning the facade of the sprawling El Dorado building at 1900 State until I returned home and looked at the photo. (A few days later, while on the way to a dentist appointment, I grabbed a shot of the artwork. It’s much more rewarding up close.) The owner of the building didn’t have any info on the artist, so I asked Nathan Vonk of Sullivan Goss gallery. “According to the public art map that I helped create last year, it was made in 1963 by Janis Mattox,” he replied. Its title is “Santa Barbara.”

Buildings, buildings, buildings…. There were so many to ponder that I must’ve gotten a little bleary because I didn’t notice the sculpture adorning the facade of the sprawling El Dorado building at 1900 State until I returned home and looked at the photo. (A few days later, while on the way to a dentist appointment, I grabbed a shot of the artwork. It’s much more rewarding up close.) The owner of the building didn’t have any info on the artist, so I asked Nathan Vonk of Sullivan Goss gallery. “According to the public art map that I helped create last year, it was made in 1963 by Janis Mattox,” he replied. Its title is “Santa Barbara.”

Also, I missed the sculpture the first time because I was busy trying to guess what some of the tenants do based on their name. Casa Serena treats addition in women; Bay Kinetic helps cannabis farms with compliance.

Also, I missed the sculpture the first time because I was busy trying to guess what some of the tenants do based on their name. Casa Serena treats addition in women; Bay Kinetic helps cannabis farms with compliance.

There are also quite a few standout buildings. Take 1801 State Street, as engaging in profile as it is straight on.

There are also quite a few standout buildings. Take 1801 State Street, as engaging in profile as it is straight on.

And the Hawkes Building at 1847 State, with its oversize arched gate to the south. “Est. 2019” is on the front, and the name refers to the developer, the late Emmet J. Hawkes, Sr. (The current tenant is architect Tom Ochsner.)

And the Hawkes Building at 1847 State, with its oversize arched gate to the south. “Est. 2019” is on the front, and the name refers to the developer, the late Emmet J. Hawkes, Sr. (The current tenant is architect Tom Ochsner.)

And the First Congregational Church at 2101 State. Look at the way the cross separates the two doorways! I even like the old-school metal canopy on the side.

And the First Congregational Church at 2101 State. Look at the way the cross separates the two doorways! I even like the old-school metal canopy on the side.

More great buildings: 1811 State Street, with its scalloped roofline (although the fenestration looks off, like the windows want to be enlarged or raised higher up).

More great buildings: 1811 State Street, with its scalloped roofline (although the fenestration looks off, like the windows want to be enlarged or raised higher up).

1625 State, which I assume is a house that has been converted to commercial.

1625 State, which I assume is a house that has been converted to commercial.

1628 State Street, which doesn’t look all that amazing from across the street but really charms up close.

1628 State Street, which doesn’t look all that amazing from across the street but really charms up close.

La Torre at 1532 State Street, with its tower, balcony, and arches.

La Torre at 1532 State Street, with its tower, balcony, and arches.

The little area next to the driveway is depressing, though. Take care of that plant or kill it already.

The little area next to the driveway is depressing, though. Take care of that plant or kill it already.

I even like 1936 State Street, despite two tenants that aren’t my jam, as no one says anymore. The filled-in archways in the middle would look so much better as windows, and if they have to be filled in, do it with more panache—perhaps referencing the striping at the 7-Eleven’s entrance.

I even like 1936 State Street, despite two tenants that aren’t my jam, as no one says anymore. The filled-in archways in the middle would look so much better as windows, and if they have to be filled in, do it with more panache—perhaps referencing the striping at the 7-Eleven’s entrance.

Oh la la, 1421 State! Designed by Carleton Winslow, it was built in 1919-1920 for the Santa Barbara Clinic. It’s a Santa Barbara Structure of Merit, and deservedly so. From the Historic Significance Report submitted to the Historic Landmarks Commission:

Oh la la, 1421 State! Designed by Carleton Winslow, it was built in 1919-1920 for the Santa Barbara Clinic. It’s a Santa Barbara Structure of Merit, and deservedly so. From the Historic Significance Report submitted to the Historic Landmarks Commission:

The white-washed walls, red-tiled tower, and arcade immediately place the building into the Spanish Colonial Revival Style. The recessed main entrance with a regal iron work door imitates the thick adobe walls common to Spanish and Mexican homes of colonial California. However, the rest of the details place the building in another category of Spanish Colonial Revival itself.

Santa Barbara’s Spanish Colonial Revival style is based primarily on Spain’s Andalusian architecture, which is simplified, vernacular, and pastoral. 1421 State Street is anything but pastoral—the classic Doric columns, the recessed entryway’s sandstone quoining and floral design below shields, and the arched windows of the second story suggest a higher form of design. You wouldn’t find this kind of building in a small Andalusian village.

Instead, the building exhibits characteristics of Plateresque style. Plateresque, or Plateresco in Spanish, translates to “Silversmith-like” and was the dominant architectural style of Spain and its American colonies in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Facades were richly ornamented—as if decorated by an adept silversmith—with floral motifs, heraldic escutcheons, sinuous scrolls, and clusters of jewelry-like patterns (“Plateresque”). Out of Santa Barbara’s many Spanish Revival Buildings, 1421 State Street is the one that references Spanish architecture of the late Gothic and early Renaissance urban styles with Plateresque detailing.

We can see this especially in the second-story façade fitted with gem-like stones. Extravagant seals with scrollwork and dentils can be found above the central window and above each of the arches of the arcade. The decorative balcony features bite-sized Doric columns, supporting Gothic or Moorish arches that abut paneled squared piers. These small intricate and exuberant details place the building firmly in a Plateresque interpretation of Spanish Colonial Revival, making it architecturally significant.

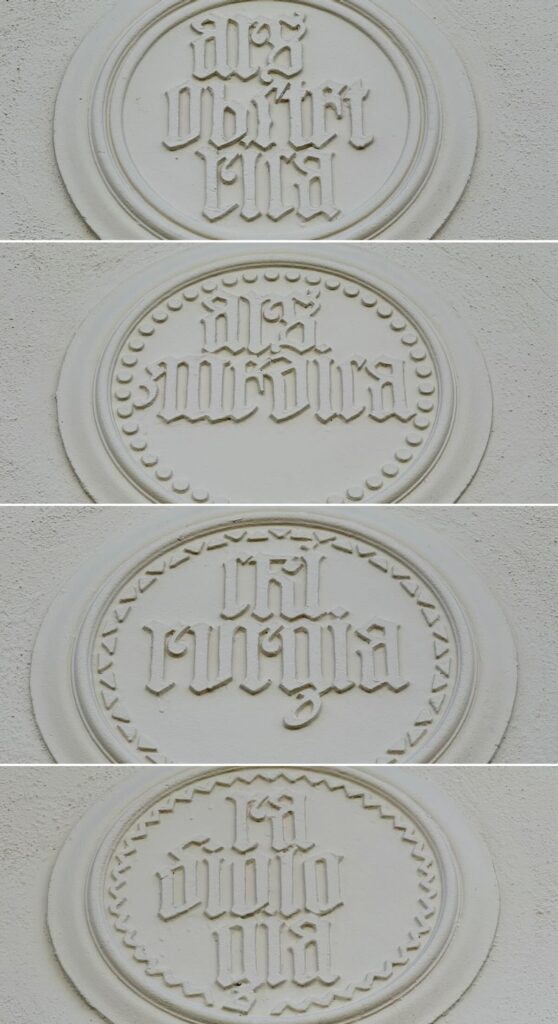

I got lost in the font while trying to figure out what’s written in Latin on the emblems on the facade, so I ran them by a friend. His answers: “ars obstetrica” (the art of obstetrics), “ars medica” (the art of medicine), “chirurgia” (surgery), “radiologia” (radiology).

I got lost in the font while trying to figure out what’s written in Latin on the emblems on the facade, so I ran them by a friend. His answers: “ars obstetrica” (the art of obstetrics), “ars medica” (the art of medicine), “chirurgia” (surgery), “radiologia” (radiology).

This sign, however, is an aesthetic mismatch and in need of updating. Reicker Pfau is a law firm; CompuVision and Vision Communications are tech-solution companies that have merged into a new entity called Converged.

This sign, however, is an aesthetic mismatch and in need of updating. Reicker Pfau is a law firm; CompuVision and Vision Communications are tech-solution companies that have merged into a new entity called Converged.

And it could go without saying—but won’t—that there is also a fair bit of architectural dreck in Mid-State. That wall on the right really kills the first building below. As for the second one (1815 State), in 2022 there was a plan to convert it to residential—specifically, “a new 16-unit, four-story residential development [that] would remodel the existing commercial building fronting State Street, demolish the existing rear commercial building, convert the front building to four residential units, and attach a new 12-unit residential building and a new 16-space parking stacker.”

And it could go without saying—but won’t—that there is also a fair bit of architectural dreck in Mid-State. That wall on the right really kills the first building below. As for the second one (1815 State), in 2022 there was a plan to convert it to residential—specifically, “a new 16-unit, four-story residential development [that] would remodel the existing commercial building fronting State Street, demolish the existing rear commercial building, convert the front building to four residential units, and attach a new 12-unit residential building and a new 16-space parking stacker.”

Some buildings aren’t what I could call obvious successes, but at least they have their own distinct character. The second one below includes four apartments; the penthouse (7 E. Arrellaga Street) sold for $3.85 million in January 2025.

Some buildings aren’t what I could call obvious successes, but at least they have their own distinct character. The second one below includes four apartments; the penthouse (7 E. Arrellaga Street) sold for $3.85 million in January 2025.

Enough with the buildings! (For now.) I did this the walk between Christmas and New Year’s, when holiday decor could still be found here and there. The runner-up: Goodwin & Thyne, where the Santa made a stronger impression in real life than it does in the photo. And I also admired the cute garage building off to the side.

Enough with the buildings! (For now.) I did this the walk between Christmas and New Year’s, when holiday decor could still be found here and there. The runner-up: Goodwin & Thyne, where the Santa made a stronger impression in real life than it does in the photo. And I also admired the cute garage building off to the side.

The winner was obviously Members Only Barber Shop, a.k.a. MOBS. Check out the little patch of “snow” on the sidewalk.

The winner was obviously Members Only Barber Shop, a.k.a. MOBS. Check out the little patch of “snow” on the sidewalk.

The lower half of Mid-State is predominantly commercial, and many of the businesses are old-school—a neighborhood market, a diner, a copy shop, a postal shop…. (Props for the latter’s sign, by the way.)

The lower half of Mid-State is predominantly commercial, and many of the businesses are old-school—a neighborhood market, a diner, a copy shop, a postal shop…. (Props for the latter’s sign, by the way.)

There’s even a newspaper (or was, because I think the Independent has moved to E. De La Guerra.

There’s even a newspaper (or was, because I think the Independent has moved to E. De La Guerra.

Speaking of which, when do we get to get rid of them? They’re an eyesore.

Speaking of which, when do we get to get rid of them? They’re an eyesore.

Back to the businesses. Mid-State was also home to a gun shop…

Back to the businesses. Mid-State was also home to a gun shop…

…and is still home to a wig shop. The brunette bob—and the accompanying facial expression—remind me of when my friend Tim would dress up as “Nadja.”

…and is still home to a wig shop. The brunette bob—and the accompanying facial expression—remind me of when my friend Tim would dress up as “Nadja.”

In December 2023, when House of Rio opened, I told them I’d swing by sometime. Another promised fulfilled! The shop has a lot of nice stuff. I can’t decide whether my preferred scent is Trophy Wife or Ranch Hand.

In December 2023, when House of Rio opened, I told them I’d swing by sometime. Another promised fulfilled! The shop has a lot of nice stuff. I can’t decide whether my preferred scent is Trophy Wife or Ranch Hand.

I still think Achilles Prosthetics and Orthotics has the best name in town.

I still think Achilles Prosthetics and Orthotics has the best name in town.

More tenants! Casa Azteca does a little of everything: “Whether you’re an individual seeking tax advice, a business owner in need of comprehensive financial solutions, or someone looking for hassle-free DMV services, you can count on us.”

More tenants! Casa Azteca does a little of everything: “Whether you’re an individual seeking tax advice, a business owner in need of comprehensive financial solutions, or someone looking for hassle-free DMV services, you can count on us.”

1727 State runs the gamut: precious metals; tax prep; hypnotherapy and life coaching; bookkeeping; makeup artists (HGM stands for Hello Gorgeous Models); cremation (“Low Cost Simple Cremation Arrangements Via Phone, Fax and E-Mail”); house painting; glass tinting; land surveying; and more.

1727 State runs the gamut: precious metals; tax prep; hypnotherapy and life coaching; bookkeeping; makeup artists (HGM stands for Hello Gorgeous Models); cremation (“Low Cost Simple Cremation Arrangements Via Phone, Fax and E-Mail”); house painting; glass tinting; land surveying; and more.

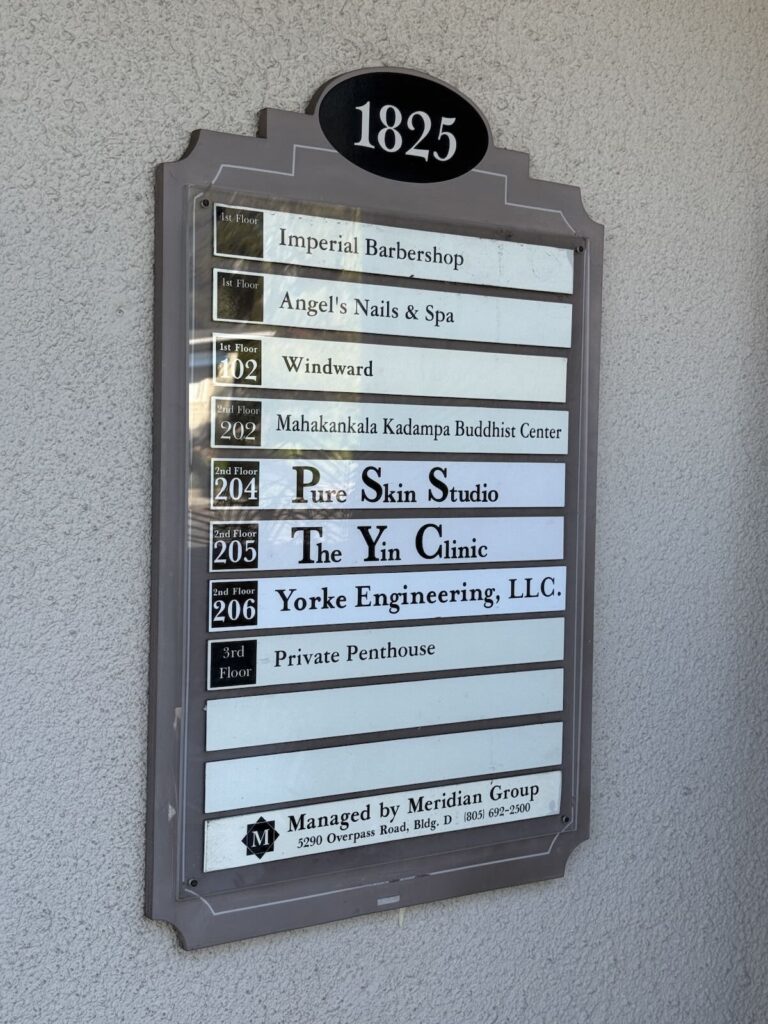

At 1825 State, I had to resist the urge to ring the bell for Private Penthouse.

At 1825 State, I had to resist the urge to ring the bell for Private Penthouse.

Is this sign part of the eye exam? Because two of those Ts are not like the others.

Is this sign part of the eye exam? Because two of those Ts are not like the others.

Above Mission Street, State Street shifts to predominantly residential. There are some apartment complexes and duplexes…

Above Mission Street, State Street shifts to predominantly residential. There are some apartment complexes and duplexes…

…but mostly houses. And a lot of them are really lovely. I didn’t focus too much on the east side of the street, because I had covered that when I walked the Upper Upper East. Nonetheless, 2304 State (at the corner of E. Pueblo), with its marvelous roof, warrants a second mention.

…but mostly houses. And a lot of them are really lovely. I didn’t focus too much on the east side of the street, because I had covered that when I walked the Upper Upper East. Nonetheless, 2304 State (at the corner of E. Pueblo), with its marvelous roof, warrants a second mention.

Here’s a photo dump of the other homes that caught my eye.

Here’s a photo dump of the other homes that caught my eye.

These two are undergoing renovations. I’ll have to check back.

These two are undergoing renovations. I’ll have to check back.

Where there are nice houses, you’ll often find nice gates.

Where there are nice houses, you’ll often find nice gates.

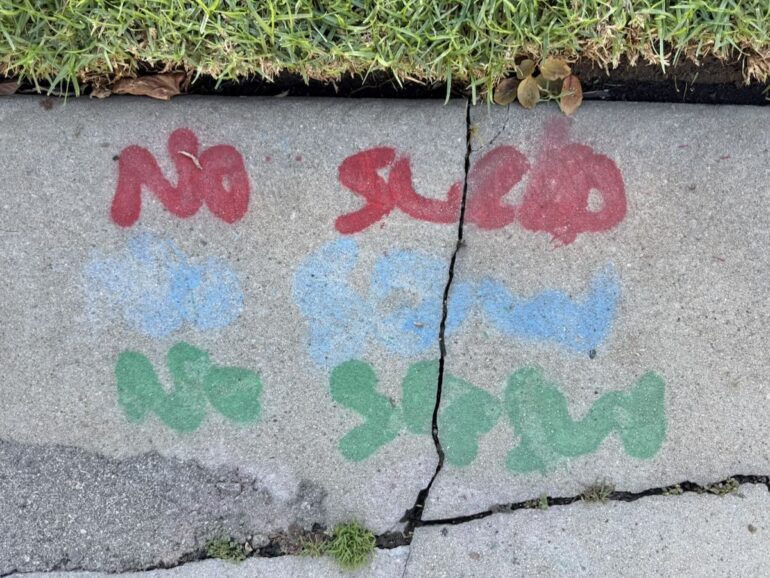

I could use some R&R, but it must’ve been beyond the boundaries of this walk. As for the second shot, any guesses? I think the first line says “no sleep.”

I could use some R&R, but it must’ve been beyond the boundaries of this walk. As for the second shot, any guesses? I think the first line says “no sleep.”

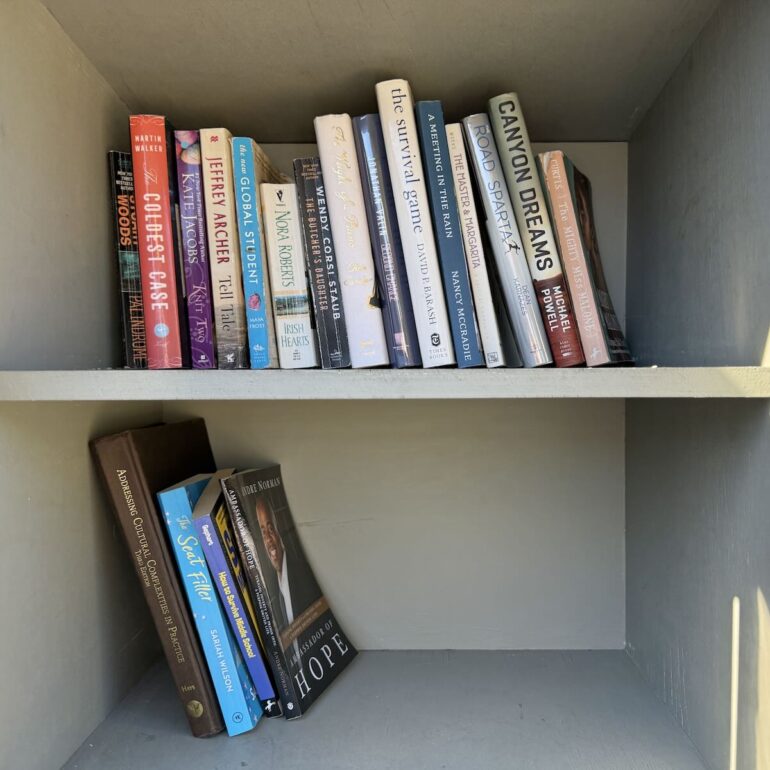

Every walk has to have a Little Free Library, although this one didn’t include anything worth noting. And I think the cart was free, but without a sign, you’re taking a risk.

Every walk has to have a Little Free Library, although this one didn’t include anything worth noting. And I think the cart was free, but without a sign, you’re taking a risk.

Speaking of signs, there were ones both amusing and sad.

Speaking of signs, there were ones both amusing and sad.

I would’ve liked to have been there when the maker of this one decided to tilt the numbers.

I would’ve liked to have been there when the maker of this one decided to tilt the numbers.

And here’s one of my very favorite address markers in town. It’s so good.

And here’s one of my very favorite address markers in town. It’s so good.

Every downtown walk also includes moments featured in Where in Santa Barbara…?, like the mosaic at the corner of State and Padre.

Every downtown walk also includes moments featured in Where in Santa Barbara…?, like the mosaic at the corner of State and Padre.

And every walk everywhere brings up questions—like what happened here?

And every walk everywhere brings up questions—like what happened here?

And at what point can wayfinding signs get removed?

And at what point can wayfinding signs get removed?

And why didn’t the city put left-turn lanes in the State Street Parkway between Mission and Constance? The double yellow lines always make me wonder if I’m supposed to turn from the driving lane.

And why didn’t the city put left-turn lanes in the State Street Parkway between Mission and Constance? The double yellow lines always make me wonder if I’m supposed to turn from the driving lane.

And why is the word “handicap” still acceptable in this usage?

And why is the word “handicap” still acceptable in this usage?

And what is this thing? I don’t think I’ve seen one anywhere else.

And what is this thing? I don’t think I’ve seen one anywhere else.

And, finally, were the streets above Mission Street once numbered?

And, finally, were the streets above Mission Street once numbered?

They were! The good folks at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum directed me to a 1995 Santa Barbara News-Press article explaining how (in the museum’s words) “a section of Santa Barbara’s streets was originally numbered; but city leaders in the late 1920s changed the numbered street names to names that were tied to people, places, events, etc. in Santa Barbara’s Spanish and Mexican history.” From the News-Press article:

They were! The good folks at the Santa Barbara Historical Museum directed me to a 1995 Santa Barbara News-Press article explaining how (in the museum’s words) “a section of Santa Barbara’s streets was originally numbered; but city leaders in the late 1920s changed the numbered street names to names that were tied to people, places, events, etc. in Santa Barbara’s Spanish and Mexican history.” From the News-Press article:

Second Street became Los Olivos. Third Street turned into Pueblo. Fourth Street was rechristened Junipero. Fifth Street became Quinto. […] Los Olivos referred to ‘the olives’ for the nearby mission olives introduced here by early missionaries, according to Rosario Curletti in her book, Pathways to Pavements.

On March 11, you can ask historian Neal Graffy about it when he gives a talk at the museum about Santa Barbara street names.

················

Walk With Me…

Downtown Santa Barbara

• The Arty Heart of Downtown Santa Barbara

• Downtown and a Little to the Left

• The Gritty Glamour of the Funk Zone

• The Upper Upper East Is Busting Out All Over

• The Presidio: In the Footsteps of Old Santa Barbara

• Brinkerhoff, Bradley, and Beyond

• Mixing Business and Pleasure in East Beach

• It’s Only Milpas Street (But I Like It)

• The Haley Corridor Is Keeping It Real

• The Small Pleasures of Bungalow Haven

• Is There a Better Neighborhood for a Stroll Than West Beach?

• E. Canon Perdido, One of Downtown’s Best Strolling Streets

Eastside

• Where the Eastside Meets the Lower Riviera

Oak Park / Samarkand

• The Side Streets and Alleyways of Upper Oak Park

• The Small-Town Charms of Samarkand

The Riviera

• The Ferrelo-Garcia Loop

• Scaling the Heights of Las Alturas

• High on the Lower Riviera

Eucalyptus Hill

• On the Golden Slope of Eucalyptus Hill

• Climbing the Back of Eucalyptus Hill

San Roque

• Amid the Saints of South San Roque

• Voyage to the Heart of the San Roque Spider Web

TV Hill / The Mesa

• Higher Education on the Mesa

• The Metamorphosis of East Mesa

• The Highs and Lows of Harbor Hills

• Walking in Circles in Alta Mesa

• West Mesa Is Still Funky After All These Years

• A Close-Up Look at TV Hill

Hidden Valley / Yankee Farm / Campanil

• Campanil is a Neighborhood in Flux

• An Aimless Wander Through Hidden Valley

• The Unvarnished Appeal of Yankee Farm

Hope Ranch / Hope Ranch Annex / Etc.

↓↓↓ A Country Stroll on El Sueno Road

Montecito

• The Westmontish Region of Montecito

• East Meets West on Mountain Drive

• A Relatively Modest Montecito Enclave

• Strolling Under a Canopy of Oaks

• Out and Back on Ortega Ridge

• The Heart of Montecito Is in Coast Village

• Quintessential Montecito at Butterfly Beach

• Once Upon a Time in the Hedgerow

• Where Montecito Gets Down to Business

• In the Heart of the Golden Quadrangle

• Up, Down, and All Around Montecito’s Pepper Hill

• Montecito’s Prestigious Picacho Lane

• School House Road and Camphor Place

Summerland / Carpinteria

• On Summerland’s Western Fringe

• A Stroll in the Summerland Countryside

• Admiring the Backsides of Beachfront Houses on Padaro Lane

• Whitney Avenue in Summerland

Goleta / Isla Vista

• In the Shadow of Magnolia Center

• A Tough Nut to Crack in Goleta

• Where the Streets Have Full Names

• The Past Is Still Present in Old Town Goleta

• Social Distancing Made Easy at UCSB

Sign up for the Siteline email newsletter and you’ll never miss a post.